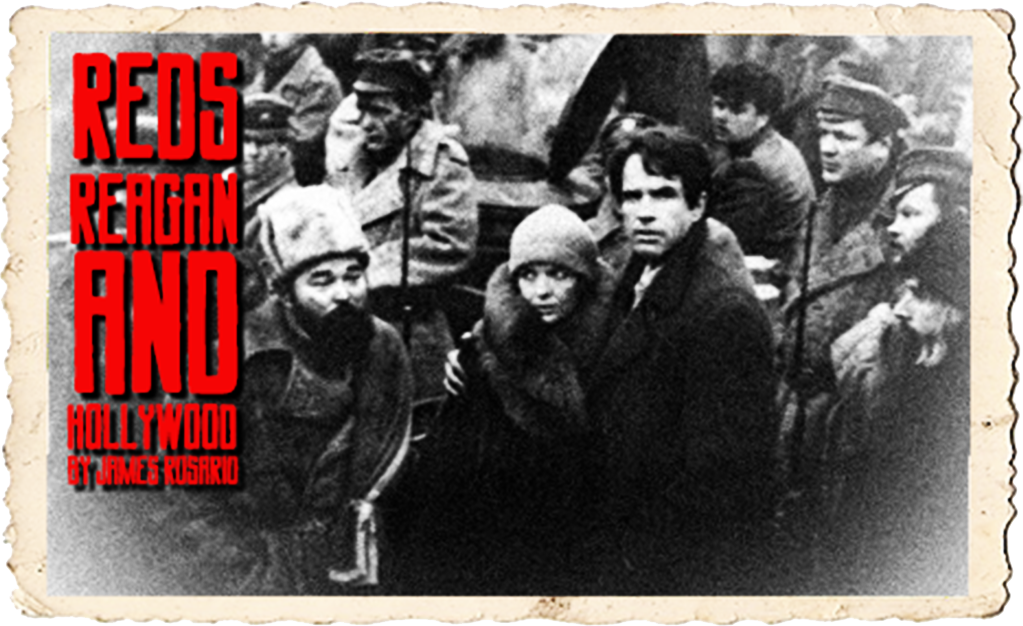

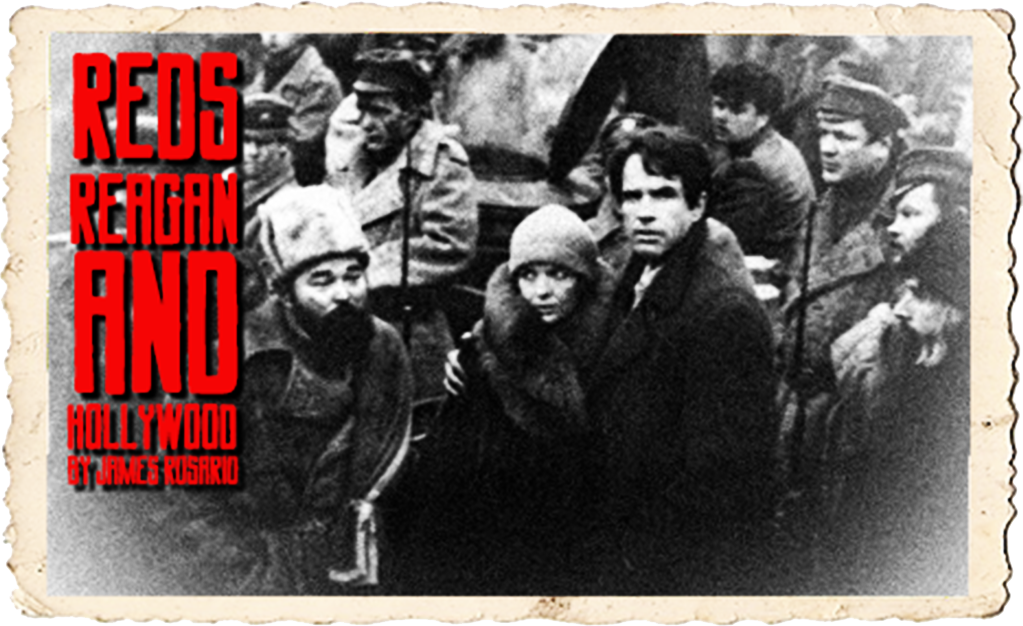

One Punk Goes to the Movies: Reds, Reagan, and Hollywood

Less than a year into Ronald Reagan’s first term, the American public was met with a very unlikely film. In a time of fear-mongering and capitalistic excessiveness, and on the eve of Reagan’s renewed Cold War efforts, Warren Beatty’s Reds seemed out of place both politically and culturally. An epic on par with David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago in breadth and scope—not to mention covering similar ground—Reds tackles the Russian Revolution from the viewpoint of a pair of affluent Americans embroiled in the idealism of anti-capitalism and a commitment to a conscientious, empowered lifestyle.

Told over several years (from 1915 to 1920), Reds cleverly disguises its politics within a sweeping love story, but the guise is thin—even if it is a better than average romance. Its true motives aren’t hard to spot, as outspoken tirades espousing the virtues of the international working-class solidarity and a crystal-clear anti-war stance place Reds at what was surely a full 180-degrees from the political pulse of the average American in 1981. Taking a bluntly pro-socialist stance in Reagan’s America was a marked risk—even in “liberal Hollywood”—but writer, director, and star Warren Beatty managed to both keep his film financially in the black and garner dozens of awards and nominations. The success of Reds is an anomaly: a giant, expensive film that contradicts American values at nearly every turn, and is yet a financial and critical triumph.

As the film progresses, so does the political fervor. Based on the real-life story and love affair between John Reed (Beatty) and Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton), Reds begins with political discussions in earnest. Theories and opinions are expounded upon by intellectuals and rabble-rousers in smoky barrooms and cramped apartments under cover of journalistic observation and the speculative uprisings. Emma Goldman is there (Maureen Stapleton), and so is playwright Eugene O’Neill (Jack Nicholson). Together with Reed, Bryant, and others, they drink and cajole through the night, discussing politics, writing plays, and carrying on liberated relationships with varying degrees of success.

Eventually, Reed and Bryant are given the opportunity to put their money where their mouths are when they travel to Petrograd to cover the 1917 revolution firsthand (the basis for Reed’s book, Ten Days that Shook the World). Reed is transformed from an “objective” observer to a full-blown communist agitator while Bryant and Goldman struggle to justify the Bolshevik’s means to their ends. For some, idealism turns to semi-reluctant fanaticism, as the realities of large-scale revolution and its aftermath take hold in disappointing ways. Others are left dejected and disgruntled at the cruelties they see with their own eyes. In the end, Reds is skeptical of full-blown Bolshevism and longs for the early days of union-led activism, which appear carefree and whimsical compared to the harshness of the revolution.

Refreshingly, Reds never paints its protagonists as heroes or saints. Its many criticisms of blustering, egotistical politicking from well-to-do white folks are well-timed, well-placed, and are aimed poignantly at both Beatty and his adopted Hollywood left, as well as the hippy-turned-yuppie culture that so disgusted him. Mirroring Beatty’s frustration with his formerly active generation, the fervor and excitement of political action dwindles and eventually dies, while the film’s romance lasts until the final frame.

The success of Reds could be a reaction to Reagan’s market-driven and fear-based policies aimed at wealth consolidation and working-class disenfranchisement, but likely, it’s much simpler. Reds is a big movie with big stars. It’s also a love story and a period piece with thousands of extras. Such movies are often risky, but when they succeed, they often do so with big returns. In the 1970s and ’80s, sweeping old-Hollywood-styled movies were still nostalgic enough to profit under the right circumstances, often regardless of the subject matter.

With an overabundance of onscreen chemistry and intelligence, along with just the right amount of schmaltz and tear-jerking melodrama, Reds was able to take hold with a public that should have rejected it. Reagan’s popularity and Iron Curtain, pro-wealth rhetoric alone should have been enough to tank an idealistic film about a bunch of America-hating liberals, but, while not exactly embraced by the average moviegoer, Reds still struck a chord. Even the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences—the governing body behind the Oscars, who rarely applauds pro-labor films—jumped on board, honoring Reds with twelve nominations and three wins, including the Best Director award for Beatty.

An appreciation of style over an admiration of substance could explain box office returns and peer recognition in an era at odds with the film’s themes and attitudes. This, however, then begs the question: could Reds be made today and retain its overwhelmingly positive response? The short answer is “no,” but of course it’s not as simple as that.

Deconstructions of wealth and power dynamics are nothing new in movies, but Hollywood rarely tackles themes that force its elite to ponder themselves in any kind of self-reflecting manor with any kind of gusto. To challenge status quo Hollywood directly—without the use of allegory, metaphor, or veiled themes—would open a conversation they aren’t willing to have: that they themselves are rich and privileged, and their political activism, while often well-intentioned, is often nothing more than lip service. Honest and open discussions about class are a rarity among Hollywood elites because these conversations might pull back the curtain and expose the farce—something the industry fears and the adoring public seems disinterested in.

With the recent success of class-aware films like Parasite, it would seem Hollywood and the American public are ready for movies that address labor and wealth in a meaningful way. However, Parasite remains largely allegorical (albeit more on the nose than usual), where Reds is a direct confrontation. Further, by pointing out the flaws of purely intellectual and often empty discourse among the privileged and educated, Reds points a finger directly at the movie industry and its hordes of smiling platitudes. Somehow, it worked in ’81, but today it could never be made. With terms like “wealth inequality,” “neo-Liberalism,” and “Late-Stage Capitalism” now firmly planted in the lexicon of American politics, thanks to long-overdue shifts in working-class priorities, monied interests are more focused than ever on holding onto theirs while denying you yours—Hollywood included. They’d rather that curtain stayed pulled shut.

But that’s not all. Even though gigantic historical epics are as old as the movies themselves, the attention span of the average ticket buyer has decreased substantially in the last two decades. Recent films like Avengers: Endgame prove that audiences are willing to sit through a three-hour movie as long as they’ve been conditioned into fandom over many years, but a period piece about American and Russian views towards labor and wealth, with no product tie-ins or CGI fever dreams, would fall very short of the necessary criteria for such a feat. With a bit of digging and imagination, one can find all sorts of allegory in Endgame (mostly praise for the military-industrial complex, but that’s another article), but when compared to a film like Reds, it can easily serve as contrasting proof that complex films with difficult themes and self-contained narratives—not to mention long—are doomed to failure in our current movie culture.

Yet Reds remains an important film—possibly more so than it did back in 1981. With cultural and political shifts happening in real-time, and Socialism being openly discussed as a viable alternative to the boot-on-the-neck form of capitalism we currently live under, its honest approach to activism, ego, and responsibility has a lot to offer. When it was released, its politics seemed far away and distant, allowing its love story and nostalgic old-Hollywood feel to carry it to success. When watched today, it’s the politics that hit home—and they’re more relevant than ever.

Originally published by RAZORCAKE.