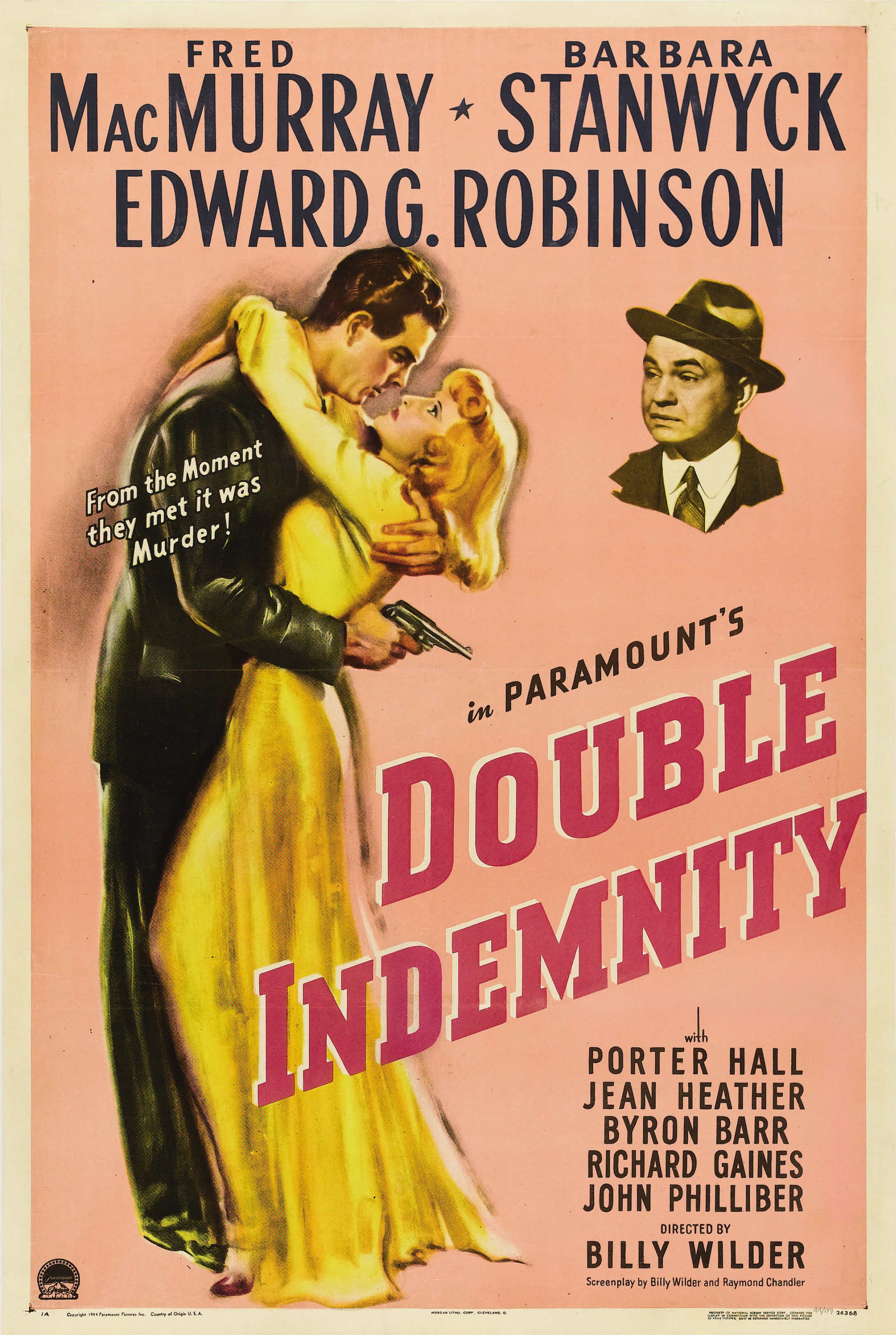

Film Review: Double Indemnity (1944)

How Dark Can You Go?

A lot has been written about Billy Wilder’s 1944 noir classic, Double Indemnity—and for good reason. That it’s one a handful of films that can be classified as the embodiment of an entire genre is an easy leap to make. In fact, if you were to go down a list of criteria for a film noir in the classic era (the early 1940s to late 1950s, give or take), I would argue that Double Indemnity checks more boxes than any other. It’s got the lethal femme fatale, the fast dialogue, the double-crosses and backstabs. It’s got adultery, greed, and optimism that turns to pessimism, and right quick, baby.

And of course, it’s got murder. But not murder committed by murderers, per se. These aren’t contract killers or hitmen. They’re regular Joes. That’s the trick of film noir, you see, its characters, while archetypal, are still everymen and everywomen. The death perpetrated up on the screen isn’t just death, it’s a question. Could you, under the right circumstances, commit murder? Billy Wilder, with co-writer and noir literary wellspring, Raymond Chandler, is asking what you would do if the perfect crime was put in your lap.

I’ve seen Double Indemnity many times. It’s one of those rare films that offers something new with each viewing. Its true nature can’t be revealed with just one (or two, or three, or maybe even ten) screenings. It’s deceptively dense. The first time around, you’re likely to focus on the plot—the scheme to kill Mr. Dietrichson (he wasn’t even given a first name! What does that tell you?). Then maybe you’ll notice how conniving Phyllis (Barbara Stanwyck) is. But wait, the next viewing might show you that it isn’t Phyllis at all who mentions murder—it’s Walter (Fred MacMurray) who first brings it up, and it’s him who runs with the notion.

Or, did Phyllis simply manipulate Walter into thinking the whole thing was his idea? Did she plant the seeds, sit back, and watch Walter water them until they grew into a full-blown scheme? This is an interesting notion, especially considering that, upon their first meeting, Walter is wise to just such a plan. He tells Phyllis that it can’t work and that she should come off it. She denies ever having insinuated such a diabolical plot, naturally, but there’s something in her eyes that suggests otherwise. Is she sitting quietly while Walter’s brain moves 100 miles-per-hour until he’s concocted the perfect crime? Or is she a devious manipulator who orchestrated the whole thing? Who is the mastermind and who is the hapless mark who fell for it hook, line, and sinker?

Wilder brilliantly leaves much to the imagination. With the benefit of hindsight, analysis, and multiple viewings, there is a lot of elements that can be interpreted in several ways. Double Indemnity is extremely manipulative. Depending on the mood or personality of the viewer, the motivations and complicity of the leads can be highly subjective.

A key scene is the one in Mr. Dietrichson’s car—and not only because it’s the point of no return for Walter and Phyllis. While Walter does the deed, the camera is focused on a close-up of Phyllis. Her expression is one of near ecstasy. That she is enjoying the moment is clear, but the question is, has she experienced this “high” before, or is this her first time? It’s suggested rather plainly later in the film that Phyllis has killed before, but it’s never proven. In either case, her expression would infer that, regardless if this is familiar territory for her or not, the thrill of it is real. She’s enjoying it, which means she’ll likely do it again, no matter how many murders she’s previously committed.

There’s another aspect of Phyllis’s involvement in her husband’s death that must be addressed as well. She quite plainly accuses Mr. Dietrichson of abusing her. With this in mind, the question must be asked: could Phyllis have been acting in self-defense when she orchestrated the death of her husband? If this is so, does that make Walter a hapless schmo who’s being manipulated, therefore alleviating him of a certain amount of blame, or is his own self-interest damning enough in its own right? How long is the shadow of self-preservation? Is it so long and dark that condemning others to save your own life is acceptable?

Whatever Phyllis’s motivations, Walter seems eager to play along. He clearly lusts for Phyllis from the moment he sees her (the dialogue gymnastics done to get around the Hays Code censors is expertly crafted). He doesn’t even try to hide it. He’s lecherous and lewd towards her, not caring that she’s married, or if anyone sees or hears him make continuous passes at her. In addition to the lust, he, of course, sees a way to make a boatload of money. Get the money, get the girl, I suppose, but it’s deeper than that. Phyllis may manipulate him into her plan (again, who played who is up for debate), but Walter clearly has evil in his heart. He is capable of murder, even without the prodding. He’s bored and greedy, and he thinks the world owes him something. In a sense, he’s the epitome of white and male privilege. Phyllis is an object for him to possess, and only a stupid man wouldn’t take the money. He believes his desires and needs supersede anyone else’s and damn the consequences. But, when he feels the heat bearing down, he strangely warns Nino Zachetti (Byron Barr) not to enter the Dietrichson home after killing Phyllis. Why he does this is a mystery, especially considering that he originally planned to frame Zachetti for the whole thing. Change of heart, or simply admitting defeat? You tell me.

Walter and Phyllis, and to a lesser extent (as far as we know) Mr. Dietrichson and Zachetti live in varying degrees of moral corruption. The morality of the film lies in Lola Dietrichson (Jean Heather) and Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson). Lola, really, is the only true innocent. She means well, has love in her heart—if misplaced—and has honest intentions. Keyes, on the other hand, has an unmovable sense of justice, which can be a form of morality. He’s nearly as cold as the rest, however, but it’s this coldness that allows him to do his job as effectively as he does. He loves Walter, and, at first, has a grudging respect for Phyllis, but when “the little man in his stomach”—what he calls his hunches—tells him that Mr. Dietrichson’s death was no accident, he’s like a lion stalking prey. He never suspects Walter, but when he hears his confession, his coldness doesn’t allow any remorse for his fallen friend. He’ll send him to the death house with no hesitation.

Are we born with the capacity for evil, or is it something we pick up along the way? Going a step further, what motivates us to walk right up to the edge? What would it take for you to jump? Wilder doesn’t answer those questions for us, but he wants us to think about them. Film Noir is dark, shadowy, and inhabited by those of questionable moral fiber, but do these social deficiencies reflect our own shortcomings or exist as a contrast—or a warning? In 1944, those working on the Hays Code committee would certainly have you believe that these types of films served as a deterrent to criminal and deviant behavior, but only naive viewers, then and now, could possibly see it that way. Exposing the dark side of humanity has its appeal. We love seeing it because it’s exciting to think about what we’re capable of or just how far we’d go to get what we want. In a sense, Double Indemnity could be seen as a personality test. Who you sympathize with and why may say something about the type of person you are.