One Punk Goes to the Movies: Spike Lee in the ’80s

When I was in ninth grade, one of my teachers gave an assignment that I can’t imagine sat well with the parents of the 99% white student body at my school. It was Black History Month, and we were to watch and write about movies made by and about Black people. In early 1993, there weren’t a lot of options to choose from, but our solitary local video store did have a copy of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, which I snatched up without hesitation. Not having yet begun the pursuit of world cinema and film history that I’m still on today, artistically speaking, Do the Right Thing was a major eye-opener for me. Writing about it was too.

Do the Right Thing was Spike Lee’s breakthrough film, but it wasn’t his first movie. Stirring the pot for over thirty-five years now, Lee is showing no signs of slowing down—even ramping things up with his last few efforts. The prolific filmmaker and New York native is no stranger to controversy, frequently inviting it in with open arms and welcoming it to stay a while. Often complicated and nuanced, the films of Spike Lee offer a look at Black American life that runs contrary to what white America is used to seeing on screen. Gone are the gangbangers and drug dealers and in are the Black middle class and Black college experience. Gone are negative stereotypes, easy answers, and white-saviorhood and in are honest observations of racism and race relations. From his debut feature in 1986 to the present day, Lee has made over two dozen films, each of them unique works of art and each of them attached to varying degrees of contention.

From my first experience with his films nearly thirty years ago to my most recent, Lee remains among my favorite filmmakers working today, or any other day. By the time I discovered him in the early-’90s, Lee already had a handful of films under his belt. The ’80s saw him grow from a gutsy film student to one of the most talked about artists in a generation, all in a very short amount of time. The three films he made in his first decade—She’s Gotta Have It (1986), School Daze (1988), and Do the Right Thing (1989)—tell very different stories, but are each grounded in Lee’s unique artistic and political vision of the world we live in.

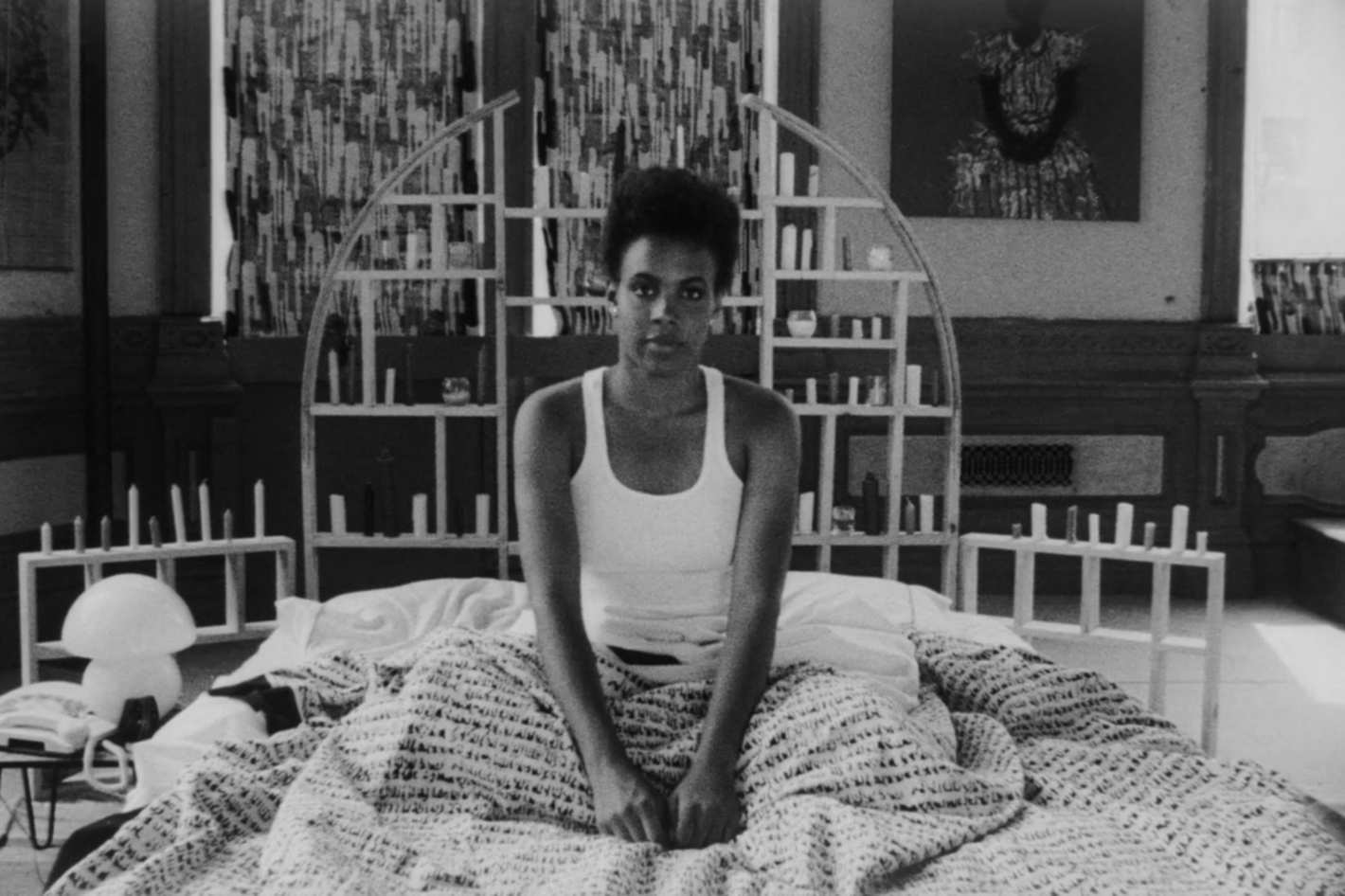

Along with the early works of Jim Jarmusch, Lee’s first film is credited with helping light a fire under the same American independent cinema scene that would go on to include artists like Richard Linklater and Quentin Tarantino. Shot like an old John Cassavetes movie (grainy black and white film, jazzy score, and Cinéma vérité-style cinematography), She’s Gotta Have It was a landmark for indie filmmakers, showcasing the heights even the lowest of budgets could achieve. With heavy nods to stylized and moody French New Wave artists like Agnès Varda (Cléo from 5 to 7, 1962) and Jean-Luc Goddard (Breathless, 1960), Lee tells the story of Nola Darling (Tracy Camilla Johns), a successful Black woman living in Brooklyn who refuses to settle for just one man. Her sexual liberation is tolerated to a point by her three suitors who all vie for her undivided attention. Naturally, this causes tension but Nola refuses to give in and settle down.

What could easily be the setup for a schmaltzy romantic comedy turns out to be anything but, as Lee deftly navigates the lives of Nola and the men she dates (played by Tommy Redmond Hicks, John Canada Terrell, and Lee himself, who would go on to reprise the Mars Blackmon role in several Nike commercials a few years later). Unapologetic about her non-monogamy, Nola states at the end of the film, “It’s really about control, my body, my mind. Who was going to own it? Them? Or me? I’m not a one-man woman. Bottom line.” She’s not cruel or vindictive. She doesn’t play the men off each other, or have an “angle” with them —she simply values her freedom and refuses to be treated as property. Couple this with Lee’s vehement rejection of negative Black stereotypes (his characters are educated entrepreneurs and artists who live happy, successful lives), and She’s Gotta Have It defines itself as an impressively progressive work.

School Daze, Lee’s next project, was met with mixed reviews from critics but still found a strong footing at the box office. Set at a fictional historically Black college but based in part on Lee’s experiences at Morehouse in Atlanta, School Daze tells the story of two cousins named Dap and Half-Pint (Laurence Fishburne and Lee). Dap is an activist whose cause célèbre is demanding the school divest from South Africa over apartheid, while Half-Pint doesn’t care much for politics, focusing instead on getting into the Gamma Phi Gamma fraternity. This dynamic leads to a host of confrontations between Dap’s politically minded set and the Gammas, who choose campus status over activism.

What’s fascinating about School Daze is that it features no white people whatsoever. Roger Ebert said of it in 1988 that it is “the first movie in a long time where the black characters seem to be relating to one another, instead of to a hypothetical white audience.” He’s right, as evidenced by the entirety of the film’s drama and conflict being relegated to the differences and disagreements between Black students, and to a lesser extent, the students and their all-Black yet conservative college administrators—not white people. However, many of the issues tackled in School Daze are rooted in, or have origins in, systematic white supremacy, such as colorism and hair discrimination. Lee may confront and expose these topics without addressing—or even directly acknowledging the white perspective on them—but that doesn’t mean white people are let off the hook. School Daze remains a film about institutionalized racism, it just takes a different path to get there and has some pit-stops along the way—such as discussions about misogyny and sexism in the Black community, the effectiveness of activism and the responsibility of participation, internalized white supremacy, and the dangers of incrementalism and tone policing. As a comedy, it doesn’t always work, but as a megaphone for an acutely political voice, it has a hell of a lot to say.

Lee’s final film of the 1980s proved a watershed moment for political cinema and is as eerily relevant today as it was in 1989. Do the Right Thing opened the door to discussions about race like no other film before it, ushering in new conversations about racial violence, bias, and unrest. Whether it was (or is) lauded, despised, or misunderstood, Do the Right Thing remains a force to be reckoned with. It is a film that should be taken literally and at face value, but also examined and mined for personal meaning. What each of us takes away from Do the Right Thing is telling, and could even be used as a litmus test for political leanings. It purposefully provides no easy answers to the questions it poses, but the point is that the questions are asked in the first place. “Always do the right thing,” Da Mayor tells Mookie. But what is that, exactly? And just who is and who is not obliged to do so?

Do the Right Thing is a beautiful, funny, and heartbreaking film that not only stands the test of time but defines the times themselves. Taking place in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, Do the Right Thing focuses on the relationship between the neighborhood’s diverse cultural and ethnic make-up on the hottest day of the summer. The long-established racial tension that lives in this microcosmic neighborhood is high but stays nonviolent for most of the day. Nitpicking, name-calling, and posturing are the extent of the day’s confrontations, but as the sun sets, things take an explosive and violent turn.

Our guide is Mookie (played by Lee), a pizza deliveryman for the Italian American-owned Sal’s Pizzeria. Through Mookie we get to know the denizens of the neighborhood, who while away the day eating, drinking, discussing, and philosophizing matters big and small. The vibrantly colored and contrasted world Lee has created is a living, breathing multicultural and multi-generational organism that thrives on community but is plagued by bias—something Lee is brilliant at bringing out. Do the Right Thing boasts no truly evil characters (except for the cops, fuck them) but nearly everyone is guilty of varying degrees of implicit and explicit bias or racism. How these biases manifest and how they are acted upon also varies, creating personal and political quandaries for us as viewers to reconcile as we absorb what we are seeing on screen. Do the Right Thing is not a roadmap to racial justice, nor does it advocate for property damage, as some critics claim. It is a question that is not easily answered, but one that desperately needs to be.

At the 62nd Academy Awards in 1990, Do the Right Thing was nominated for only two awards, despite it being the most talked-about film of the year. Danny Aiello received a supporting nod (but did not win) for his role as Sal, and Lee himself was nominated for Best Original Screenplay. In what could be considered the modern origins of the #OscarsSoWhite movement, Lee lost the Oscar to Driving Miss Daisy, a film nearly the political opposite of Do the Right Thing and a classic example of Hollywood patting itself on the back for being the open-minded bastion of platitudes that it is.

As Lee headed into the ’90s, the controversies surrounding his films would ebb and flow, but his output remained a creative and abundant force. The ’90s would see him make eight films, with subjects ranging from Malcom X to the Son of Sam murders. As his technical prowess and box office viability increased, so did his budgets. But, as many of us know, it’s often the early work of an artist that proves the most genuine and intriguing.

Originally published by RAZORCAKE.