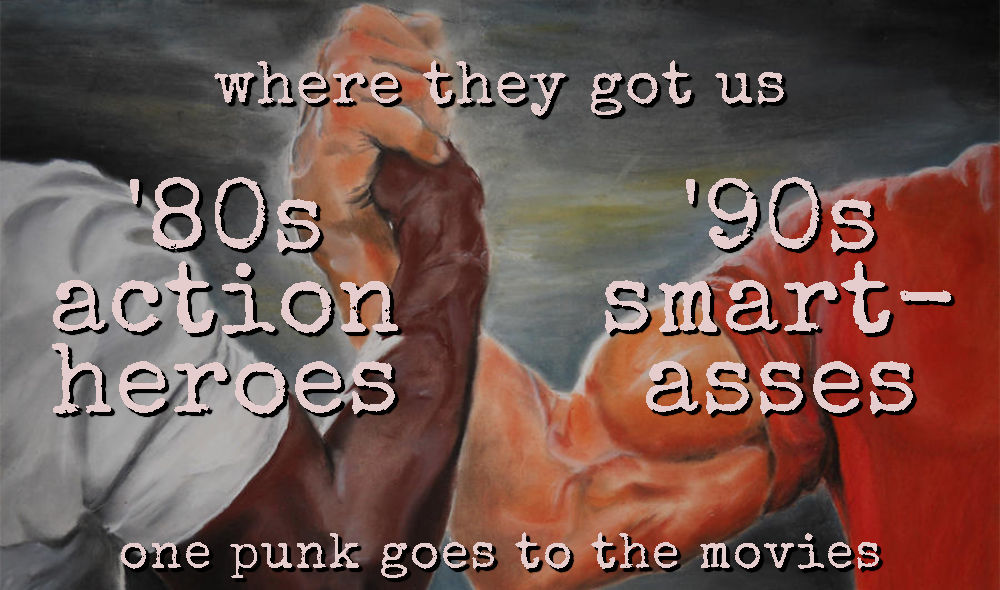

One Punk Goes to the Movies: ’80s Action Heroes, ’90s Smart-Asses, and Where They Got Us

As a member of Generation X and a lifelong movie fan, my ideas surrounding heroes and heroism have been heavily skewed by ’80s action movies. Whether it be villainous thieves hijacking an office plaza or an alien menace stalking its prey in the jungles of Central America, the movies of my youth taught me that machismo and gumption—along with a steady cache of one-liners—were all one needed to survive nearly any situation. Our heroes made us daredevils first and considerate human beings second; seekers on the move with no discernable destination, but with an undefined yet strong sense of justice. Our heroes showed us that the individual can weather any storm or army, and that the good guys win not through measured conversation or logic, but by obliterating the bad guys with bullets or bombs.

This mindset ran rampant across an entire generation of boys who longed to be independent, strong, tough, and funny, just as the stoic resolve of John Wayne and other conservative stars had molded the previous generation into closed-off, conformist drones. By the early-1990s, the individualism taught to us by our childhood movie heroes transferred rather seamlessly into an appreciation for the antiheroes emerging from the independent movies that would come to dominate the decade. As we entered into our teens and twenties, the jingoistic aspects of our action stars gave way to the thoughtful, witty banter of a new kind of hero: the smart-ass—that chattering, loudmouthed force to be reckoned with that took ’90s cinema by storm.

These new movie heroes were just as audacious and lively as their counterparts, but the situations they found themselves in were rarely as violent. Of course, this wasn’t always the case (the early films of Quentin Tarantino proved plenty bloody and mouthy), but by and large, the ’90s smart-asses got themselves into trouble by the sheer force of their uncontrollable wit—and got themselves out of it on the back of that very same cleverness. Names like Quentin Tarantino and Kevin Smith—and other notables such as Richard Linklater (Dazed and Confused, 1993), Larry Clark (Kids, 1995), and F. Gary Gray (Friday, 1995)—call up long-winded and highly quoted diatribes that were, at the time, meant as observational comments on everything from Star Wars to European cheeseburger consumption (along with more substantial issues like drug use and relationships), but have since entered into the pop culture lexicon based on the strength of their timeless appeal. ’80s stars like Bruce Willis, Sylvester Stallone, and Arnold Schwarzenegger are quotable, sure, but the staying power of their words is nothing compared to a “Royale with Cheese.”

These new cinematic heroes differed from their predecessors in ways beyond their sharp-witted turns of phrase, though. With a massive generational and economical shift underway, priorities and politics naturally shifted as well. For example, in the 1980s, it was almost a given that an action hero’s day job would be that of either a cop or a soldier. There are notable exceptions, of course, (Harrison Ford’s Indiana Jones and Kurt Russell’s Jack Burton come to mind), but by and large, no matter how rebellious, or how much of a “loose cannon” an ’80s action hero was, they almost always operated within an authoritarian hierarchy. (Disturbingly, this realization could account, at least in part, for why Baby Boomers—who were in their thirties and forties during the ’80s—now have such a willingness to submit to authoritarian control, as evidenced by the numerous political and cultural hills they’ve chosen to die on in the last thirty years.)

Additionally, the movie battles fought in the ’80s were always epic struggles against all odds, and usually tinged by some form of xenophobia, racism, or conservatism. That all changed in the ’90s. As the incomes and prospects of Gen X dwindled, so did the size of their battles. Gone were the world-saving hijinks of emotionless yet lovable tough guys, and in were the small-time crook, the gas station clerk, the stoner, and the lovable loser. Admittedly, these new heroes were often just as emotionally stunted as their forebears, but at least they were aware of the world around them and their diminished place in it.

In hindsight, however, most ’90s heroes did us no favors, despite their entertaining banter. In contrast to the heroes of previous generations, the smart-asses of the ’90s chose not to play the game, and in doing so, taught us that being witty and smart was all one needed to survive. In reality, we were (and are) much more savvy, nuanced, and intelligent about politics than our parents ever were (i.e. we are much better at questioning authority and thinking for ourselves), but we failed to act on much of it, if any. Our rebellion was choosing not to participate in a fucked-up system, and as a result, a whole generation went without political representation—something we are now paying dearly for. We may have rejected the racism, sexism, homophobia, and greed of our parents, but obvious truths aren’t worth much without loud, continuous voices to scream them.

Was our lack of political engagement entirely the fault of Randal from Clerks or Jules from Pulp Fiction? Of course not—just as the willful submission to authority and flag-worshipping of our parents isn’t entirely the fault of Rambo or John Wayne. But, the independence from authority depicted in ’90s independent films fueled our own rejection of accepted norms by showing us that life could be worth living without the lofty (and now completely unattainable) goals of our parents. We may have dropped the ball by choosing non-participation, but, despite outward appearances or outcomes, our rebellion was, and remains, sincere, thoughtful, and based firmly on the betterment of society. Is there anyone out there who can effectively or realistically argue the same for our parents? And what will our kids say about us?

Originally published by RAZORCAKE.