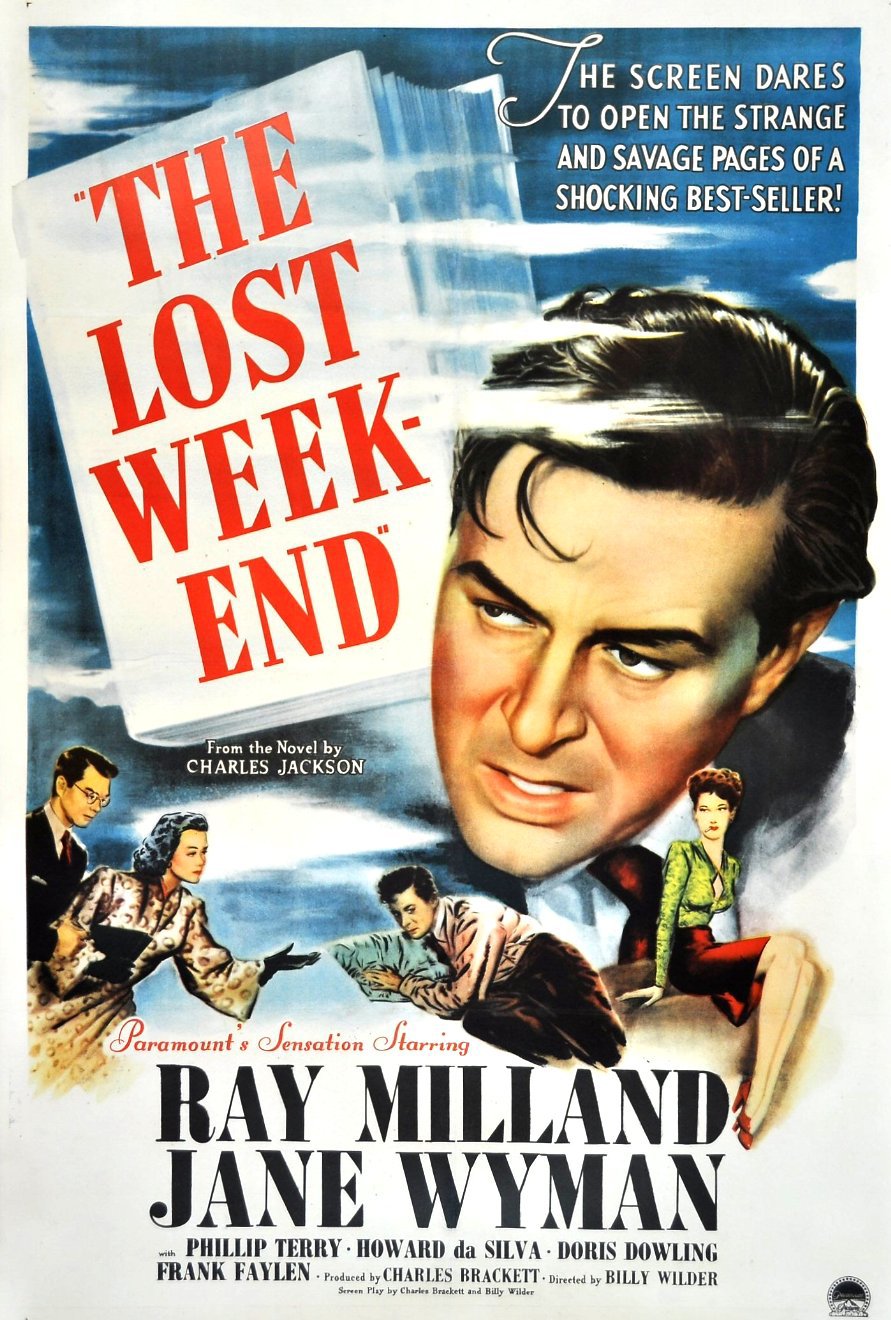

Film Review: The Lost Weekend (1945)

For someone, such as myself, who used to have quite a thirst, Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend is an especially poignant film. I feel a special kind of kinship to Don Birnam and his struggles with the bottle and the problems that arise from one’s dependency on it. The alcoholic writer (played brilliantly by Ray Milland) walks us through the depths of dependency and regret as he stumbles toward hope and redemption. For some, the 1940s presentation may dilute the potency of the mixture, but for my money – as someone who’s been there – Wilder and Milland nail it head on.

The inaccurate portrayal of drunkenness on film is one of my biggest pet peeves. People who act drunk in movies rarely look or sound realistic. They’re usually wildly gesticulating, hiccupping, or otherwise slurring their speech in comedic ways that don’t represent the severity of intoxication. The Lost Weekend takes a much more authentic approach. Alcoholics are often people who view drinking as a ritual, not just a means to an end or an accidental occurrence. There’s a deliberateness to the act that delves into the psychological. It’s not all about getting a good drunk on.

When we enter the story, Don is about to leave on a weekend trip with his brother Wick (Philip Terry) and girlfriend Helen (Jane Wyman). It’s quickly made clear that Don isn’t as sober as he lets on, as he’s got a bottle dangling from a string outside his apartment window. Don convinces Wick and Helen to leave on a different train so he can have some time alone. He then heads straight to Nat’s Bar, where he begins a long, fateful weekend.

While The Lost Weekend may not be a typical Film Noir (no femmes fatales, adultery, or murder), it certainly hits enough of the psychological markers and cinematic nuances to fall squarely into that category. Angular shadows and escalating tension pervade as Don falls deeper and deeper into his black pit. The climax – a horrifying and cerebral manifestation of inner fears – is a frantic stab of paranoia and pain. Don is warned of the oncoming experience but does not heed the advice. Instead, he pushes on into a vicious dive until his humanity is all but lost. Film Noir loves flawed, fatalistic characters who lurk on the edges of societal acceptance and Don Birnam exemplifies these qualities without ever firing a gun.

Along with the discordant score by Miklós Rózsa and brilliant, gritty cinematography by John F. Seitz, The Lost Weekend becomes an early standard-bearer for the depths addiction can plumb. Later films like Leaving Las Vegas (1995) or Requiem for a Dream (2000) may pick up where Wilder left off (and in the case of Requiem, take it to new levels of nightmarish reality), but The Lost Weekend faced these issues as World War II was ending and a lot of soldiers were coming home with undiagnosed PTSD and unhealthy coping mechanisms. And while the film may have shied away from the homosexual overtones of the source material (the best-selling novel by Charles R. Jackson), it still tackles an issue that needs addressing even today.