Film Review: Russian Ark (2002)

Maybe you’ve heard of Russian Ark. In case you haven’t, it’s unique in one remarkable way: it consists of exactly one continuous 96-minute shot. No cuts, no editing. This might not be so remarkable if it were a monologue, or was limited to only a few actors, or only one or two sets, but that is not the case. Russian Ark was shot in 33 rooms of the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, employs over 2,000 actors, and three entire orchestras—and they only had one day to get it right. Director, Alexander Sokurov, cinematographer and superhuman, Tilman Büttner, the unseen and constantly moving sound and lighting crews, and the host of actors got the shot on the fourth take, as the light of the day was dwindling. They would not have had time for a fifth try.

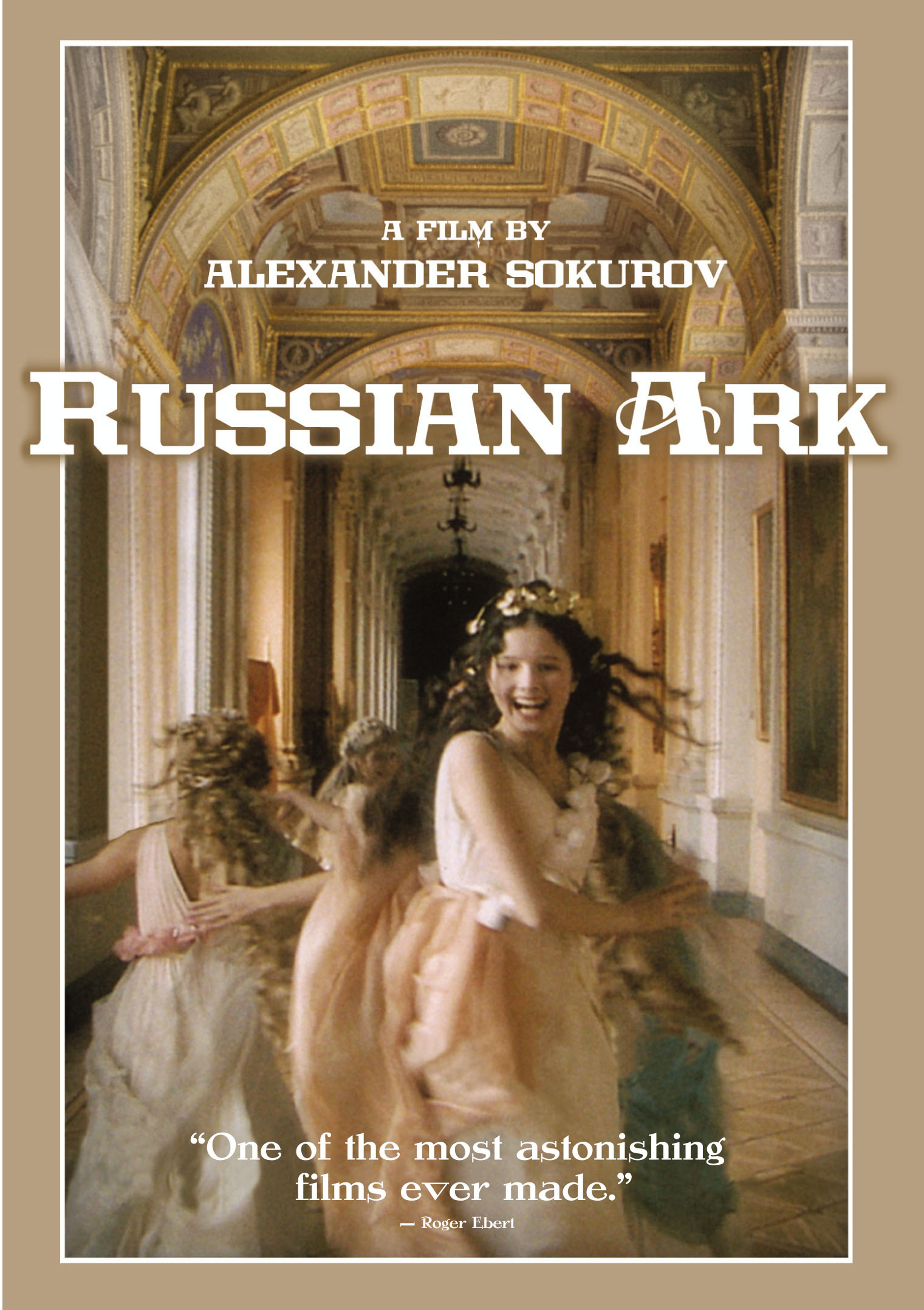

The film is beautiful and dreamlike. In it, we see through the eyes of an unseen narrator (voiced by Sokurov) who follows and converses with a European aristocrat (Sergey Dreyden) through the many elaborate halls of the Winter Palace. The narrator is invisible to everyone but the European (who can be seen and interacted with by the palace patrons). The two argue and bicker about Russia and its history as they lead us through 300 hundred years of art, ceremony, and tragedy. The European, you see, doesn’t hold Russia, its people, or its culture in very high regard. He continuously demeans nearly everything he sees on his (and our) journey.

Think of Russian Ark as a vivid and lucid dream. The narrator knows that he is dreaming, perhaps, but is powerless to change his trajectory. He is at the mercy of both the European, and what seems to be a complex, yet fluid path through Russia’s history. If Russian Ark is a dream, it’s a fragmented one and open to interpretation, as dreams are. The story told is not chronological and quite incomplete—offering only glimpses at such figures as Catherine, Peter, and Czars Nicholas I and II—but gives us a feeling of what their lives may have been like in all its splendor and pomp. We aren’t offered the whole picture, but we don’t need to be.

As is, the film mostly works, but what if it didn’t employ the unique “one take” approach? Would it be as interesting, or is the “gimmick” its main point of interest? The way I see it is simple: who the hell knows? On one side, without the single shot technique, the story may have been uninteresting and uncompelling. The only tension in the film is happening behind the camera (you can almost hear everyone holding their breath and feel thousands of fingers crossed). On the other hand, had the film been shot more traditionally, it may have had an opportunity to shine in other cinematographic ways. What I mean is, by necessity, every shot is at eye level—and this can get stale at times. So, having the opportunity to spice things up with varied camera angles may have added to the experience.

But, it was shot the way it was, so there’s really no point in arguing it, is there? The boldness of the idea is half the battle, and maybe, half the point. There are glitches (extras on many occasions look directly into the camera, and lights reflect awkwardly off paintings), but, nonetheless, it’s quite a feat. The entire film is an event, and it should be witnessed.

The final third culminates in a grand ball, which, in an ordinary film, might signify an ending. Not so here—not quite anyway. When the dance concludes, the guests must leave the palace, and so must we. What we witness is nothing short of miraculous. Thousands of extras, all dressed in exquisite period costumes, line the hallways and decorative staircases leading out of the building. We pass them all on our way out, all the while catching glimpses of the beauty and imposing architecture that makes up the impressive place we have just toured. Outside lies the sea, and our journey can go no further.