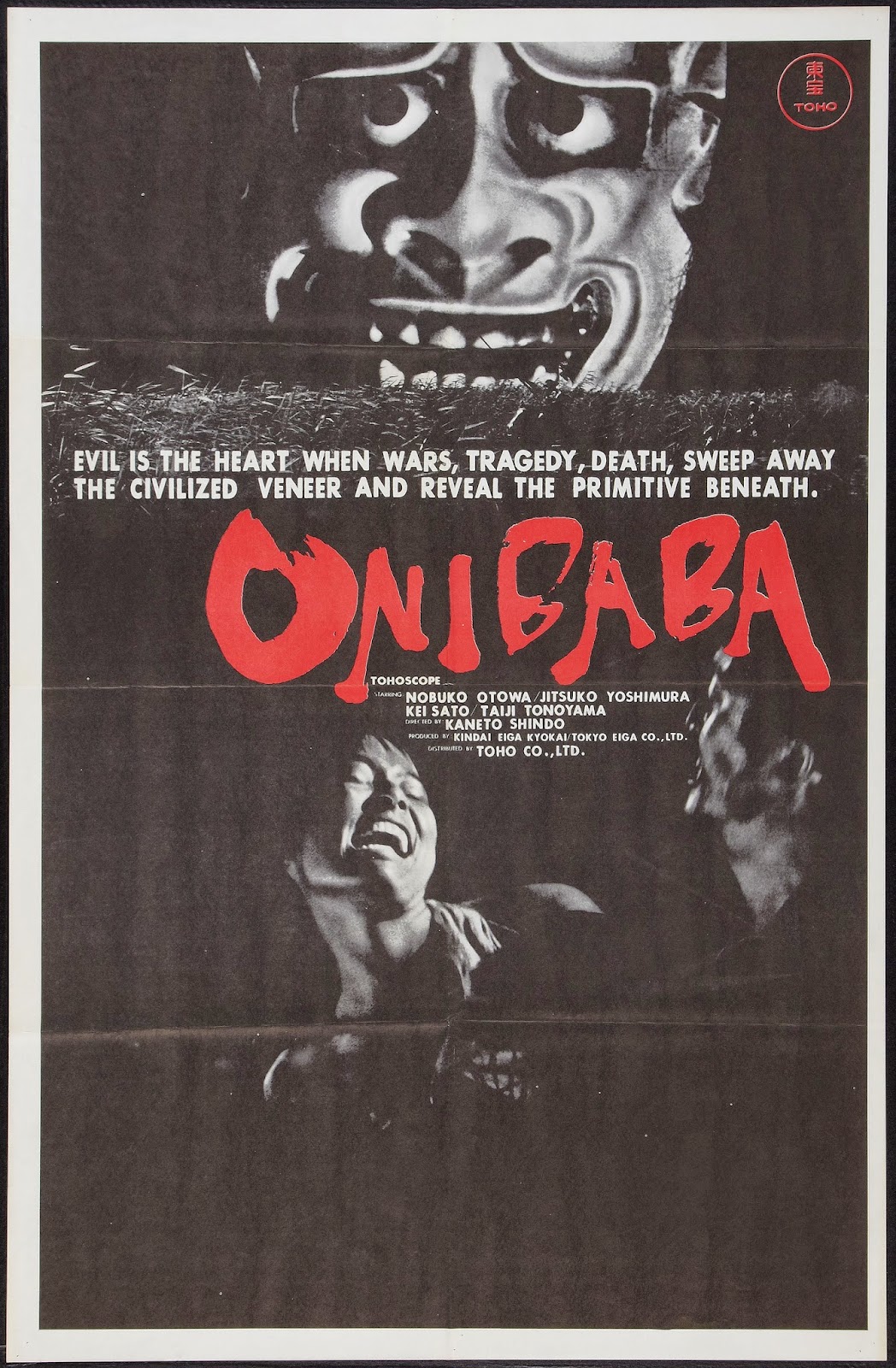

Film Review: Onibaba (1964)

It is a full ten minutes before a human voice is heard in Kaneto Shindo’s dark tale of desperation and primal instincts. In that time, however, the world we are about to inhabit is described in disturbing detail. Two soldiers are running through a field of tall weeds. When they pause to fight each other, they are killed by blades that propel through the reeds by unseen hands. When they are dead, their bodies are stripped by scavengers, and then dumped into a large open pit. In this time of war, necessity permits crimes and atrocities that would never have been considered otherwise. In an effort to survive, the primitive quickly overtakes the civilized.

Onibaba never leaves the field of overgrown grass in which the film opens. The closest it gets is to briefly go underneath it into the deep hole strewn with dead bodies and skeletal remains. The wind is always blowing in this landscape, and the sky is rarely seen, as the weeds are taller than any person. There is a war raging outside of this field, but there are devils and demons lurking within. Proceeding with caution is advised.

Sin seems to be on the director’s mind—its indulgence and its punishment. In this bleak world, partaking in delights is punishable by death, but jealousy has a high price to pay as well. The two scavengers are never named. The closest we get is that one of them is the mother of Kichi (Nobuko Otowa), and the other his wife (Jitsuko Yoshimura). They’ve managed to eke out a living killing lost samurais who wander into their field from the nearby battles and then selling their equipment to a black-market dealer (Taiji Tonoyama). One day, a fellow farmer, Hachi (Kei Satô), who was conscripted into the army with Kichi, returns to the fields. He informs the women that their son and husband was killed and that he barely escaped with his life. Soon, Kichi’s mother is jealous of the relationship growing between her daughter-in-law and the lazy, loutish Hachi.

Kaneto Shindo’s cameras capture the struggle and brutality of mid-fourteenth century Japan in stark black and white. Figures move in and out of shadows with clever displays of light and contrast. The eyes of each character are deeply examined, often with the light source coming from the bottom with shadows cutting off the tops of heads. This technique elongates each gaze, adding to the tension and dipping our feet into the surreal. The cinematography (by Kiyomi Kuroda) has both moments of smooth movement and jagged jump-cuts. If the film weren’t so obviously Japanese, the cameras and editing could be mistaken for French New Wave or German Expressionist. How’s that for style?

Further pushing the film into the realms of irresistible weirdness is its score by Hikaru Hayashi. Traditional Japanese drums are mixed with jazz-influenced instrumentals, creating a juxtaposition that’s capable of making the hair on the back of your neck stand straight up. Strange screams and grunts are also added in, invoking something ghostlike and inhuman. Long moments of silence are sliced through with jarring blasts of noise that cut the night right in half. It’s a clash of sounds that forces attention.

There may be sex, but there’s certainly no romance or sensuality. Hachi and Kichi’s wife are far from in love, but the ravages of war have put them together, and they find comfort in that. Relationships, all of them, are more animalistic than familial or romantic. All action is taken in order to survive, including Kichi’s mother’s deception aimed at separating the two young lovers. Their world is small, and with their livelihoods depending on the very bad luck of lost soldiers, they strive to control it as best they can —which includes, sometimes, invoking demons. With your survival on the line, however distasteful or despicable it may be, is it a sin to endure? Should you be punished for it? If so, by whom or by what?