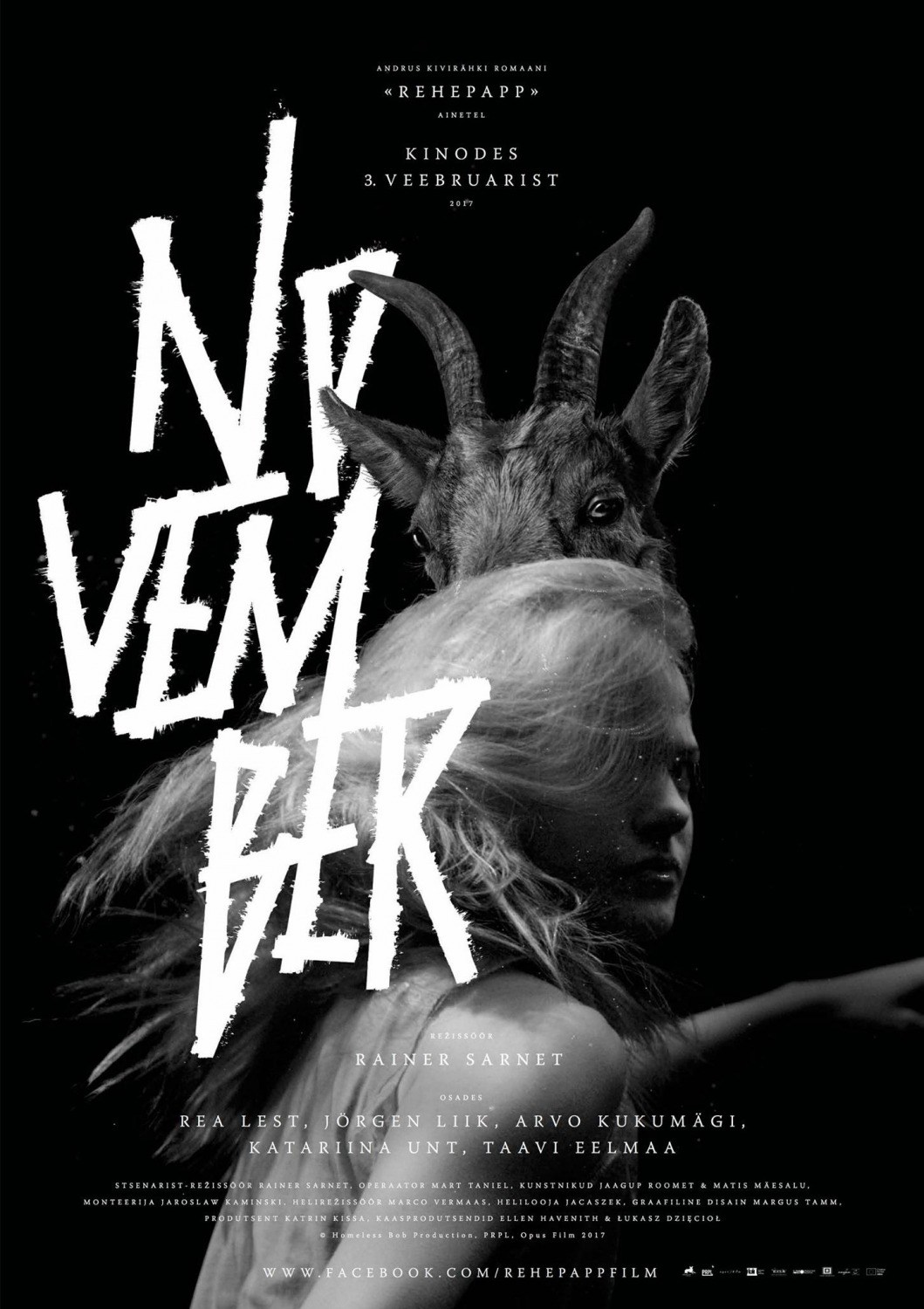

Film Review: November (2018)

I wish “Estonian Folk Tale” was a viable genre. At the very least, I want one more entry to compare November to because I am one-hundred percent fascinated with Rainer Sarnet’s weird, magical, and sometimes terrifying film. The world Sarnet has crafted (from the novel Rehepapp ehk November by Andrus Kivirähk) is one rich with legend, mystique, and cobbled together mechanical servants who turn violently on their masters when they get bored. If that sounds out there, it is, and it should, but along the way, there are plenty of visual treats to grab onto and plenty of parables to consider. November is a beautiful and eerie piece of filmmaking whose strangeness feels as natural as its diabolism.

Usually, film depictions of witchcraft, occult, or pagan rituals are treated as taboo or something to be shunned and persecuted, but refreshingly, that’s not the case in November’s 19th-Century Estonian setting. Peasants in a small, starving village regularly make crossroads deals with devils for souls to power their “kratts” (beings made of hay, sticks, and farm tools that perform menial tasks and steal from neighbors at their owner’s behest), as well as barter for potions, visit with dead relatives, and all other manner of sorcery. These are not, however, evil sorcerers or blasphemous fiends – they’re God-fearing Christians. They simply haven’t given up all the old ways yet. And what’s most interesting is how every day and commonplace their practices are. No one is ostracized or even criticized for meeting with a demon or using a kratt to steal a cow. Everyone does it. It’s no big deal.

That’s not to say it isn’t a frightening affair to witness. I wouldn’t categorize November as a horror film, but many of its elements borrow from the creepier and more atmospheric aspects of the genre. Comparisons to The Witch (2016) wouldn’t be off the mark in terms of style and tone but wouldn’t be truly apt either. The superstitious folklore at the heart of November is much more reminiscent of films like The Fast Runner (2001) or Onibaba (1964) – with shades of the latter making many appearances in my observation. I find it intriguing that folklore from two countries so far removed from each other can conjure up so many of the same emotions from me – and that two films made 55 years apart can do the same thing. Cinema is funny like that.

There is a story, but it largely exists to move us from one strange ritual or archaic practice to the next. The love triangle between Liina (Rea Lest), Hans (Jörgen Liik), and the Baroness (Jette Loona Hermanis) is as good as any (made better by lycanthropy and satanic pacts) but falls somewhat flat in the emotional connection category. I did enjoy the O. Henry-esque nature of the love story, but it’s the film’s other oddities I found myself drawn more deeply towards. The lives of the villagers (and to an extent the lords who rule over them) is a seemingly never-ending struggle for survival on one level or another. I could watch all day as they comedically struggle to ward off a plague or attempt to coax the spirits of relatives to reveal their secrets. It’s a parade of entertaining exercises of perseverance and greed in the face of starvation and class loyalty. It’s funny and it’s beautifully shot, but through all that, it’s haunting. It’s not just that there are ghosts and other mysterious entities, it’s that the entire setting seems haunted by superstition and desperation. Maybe one begets the other, I don’t know. Every character treats these mysticisms as every day, so we too feel that the frozen countryside and its beings are as organic as the dirt.