Film Review: Godzilla Minus One (2023)

In the years following Ishirō Honda’s original 1954 production of Godzilla, but before Takashi Yamazaki’s 2023 reimagining of the monstrous kaiju, there have been a lot of disappointing films made starring the famed “King of the Monsters.” In fact, there have been 38 Godzilla movies made in the nearly 70 years between the two, each with its own degree of cult following or eye-rolling disdain.

For decades, Hollywood has been trying to capture the magic of everyone’s favorite atomic superbeast but, perhaps predictably, has failed to even come close to what Honda, some miniatures, and a big rubber suit managed all those years ago. Hollywood Godzilla movies are hardly worth the gigabytes they are made with—especially when compared with the cleverness, camp, and meaningful commentary found in the original.

On the Japanese side of things, Hideaki Anno and Shinji Higuchi’s 2016 Japanese production of Shin Godzilla—which uses a voyeuristic found footage approach and plenty of rubber suits of its own—comes closer than anyone to Honda’s vision, proving, perhaps definitively, that Hollywood simply does not understand Godzilla and never will. Where U.S. productions go brain dead when it comes to the many things Godzilla movies could allegorically address, Shin Godzilla is a clear comment on the then-recent Fukushima disaster. It’s at least saying something about the world its destroyer is, well, destroying.

But then, like a shining explosion near Bikini Atoll, comes Takashi Yamazaki’s Godzilla Minus One, a film I didn’t even know I’d been waiting for, but one that makes my heart soar with radiant atomic energy all the same.

Putting aside for a moment that Godzilla Minus One is a film that features a giant, atomically charged dinosaur, it’s difficult for me to put into words how and why I‘m fascinated by movies and books about post-war Japan and the aftermaths of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the fire-bombing of Tokyo, and the Pacific theater of World War II in general. I suppose it’s partly because my grandfather served there during the war, but it’s also because of my love for Japanese punk rock and ‘80s anti-war bands like Discharge, Crass, Crucifix, and the Peace Punk movement as a whole. Mix this with post-war and allegory-rich Japanese cinema, and I now stand before you as the man I am.

(On a side note, bands like Discharge have a way of cutting through the bullshit and getting straight to the terrifying heart of ongoing nuclear paranoia like no other protest music ever could. Their no-nonsense, minimalist approach to the very real threat of annihilation is as haunting as it is epic.)

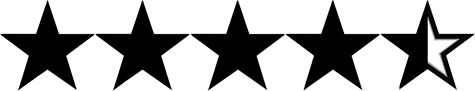

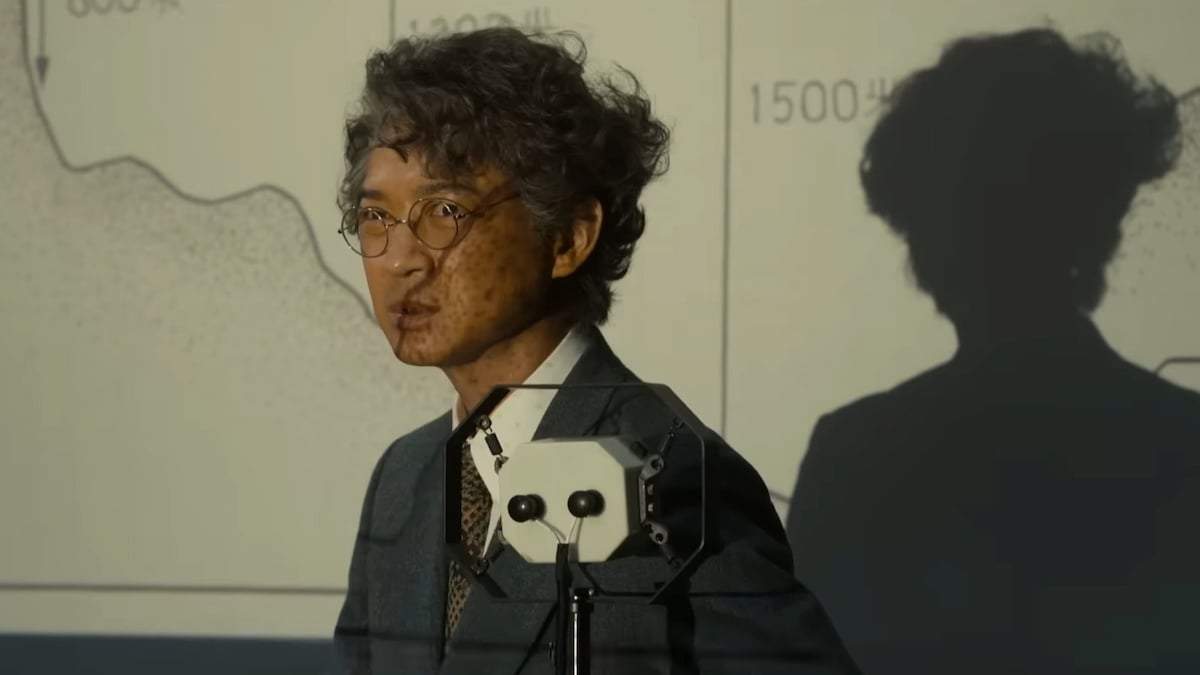

Just like Honda demonstrated back in 1954, there’s nothing like a giant monster to help tap into a nation’s collective fears and apprehensions—a ball Yamazaki grabs hold of and runs with to great effect. Taking place mostly in the bombed-out remains of Tokyo in 1947, Godzilla Minus One follows the make-shift family that forms between former kamikaze pilot Kōichi (Ryunosuke Kamiki), Noriko (Minami Hamabe), a young woman who lost her family to the bombings, and orphaned baby Akiko (Sae Nagatani) as they navigate life after wartime. Their lives are hard, but they make due on the strength of their resolve and the silent knowledge that they aren’t alone in their trauma and survivor’s guilt.

Wartorn Tokyo is not an easy place to survive, but just as Kōichi, Noriko, and little Akiko start to catch their stride, the same destructive force that destroyed their homes in the first place rears its ugly head in the form of an ancient sea creature now mutated by U.S. atomic testing in the Pacific. Once again, the United States, through egomaniacal self-interest, will be the cause of Japanese mass destruction. With no one to help, not even their own ineffectual government, it’s left to the people of Tokyo to handle the problem themselves.

If you’re familiar with the original film, Godzilla Minus One offers no shortage of homages and easter eggs—not to mention the fantastic score by Naoki Satō and plenty of nods to Akira Ifukube’s music from the 1954 production—but the franchise’s long history isn’t its only influence. Steven Spielberg’s Jaws plays a major role in making Godzilla Minus One the terrific movie it is (it may be the shark that made you watch Jaws the first time, but you wouldn’t have watched it again and again if not for the characters tasked with bringing it in), but other films like Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru (about a man who chooses to live life to the fullest after being diagnosed with a terminal illness) and the surrealist works of animator Hayao Miyazaki are other important factors. The emotional variety found in these distinguished films breathes new life into a franchise that many seem to have forgotten was born out of the same kind of powerful sentiment.

But, as important as Yamazaki’s ability to harness his influences into a moving depiction of a devastated nation’s somber mood might be, Godzilla Minus One also boasts the best visual effects I’ve seen in years. In a CGI-dependent industry, Godzilla Minus One sets a new standard for what visual effects can convey, all while honoring the look and feel of the original films. Where other Godzillas bear the telltale marks of complete digital fakery, Yamazaki’s monster is beautiful and realistic, and at times, even brilliantly resembles Honda’s original rubber-suited version in the best ways possible. Look into the eyes of Yamazaki’s Godzilla, and you’ll see a creature painfully lost and confused, driven by an unexplainable need to destroy. Look into anyone else’s, and there’s nothing but a blank stare.

In an awards season that’s sure to see mass murderer J. Robert Oppenheimer honored over and over again, I urge you to balance any Nolan-styled hero worship you may be feeling with not just Godzilla Minus One or Honda’s original, but with as many post-war Japanese movies you can get your hands on. It’s time to start seeing things from the other side of history.

And listen to Discharge while you’re at it.