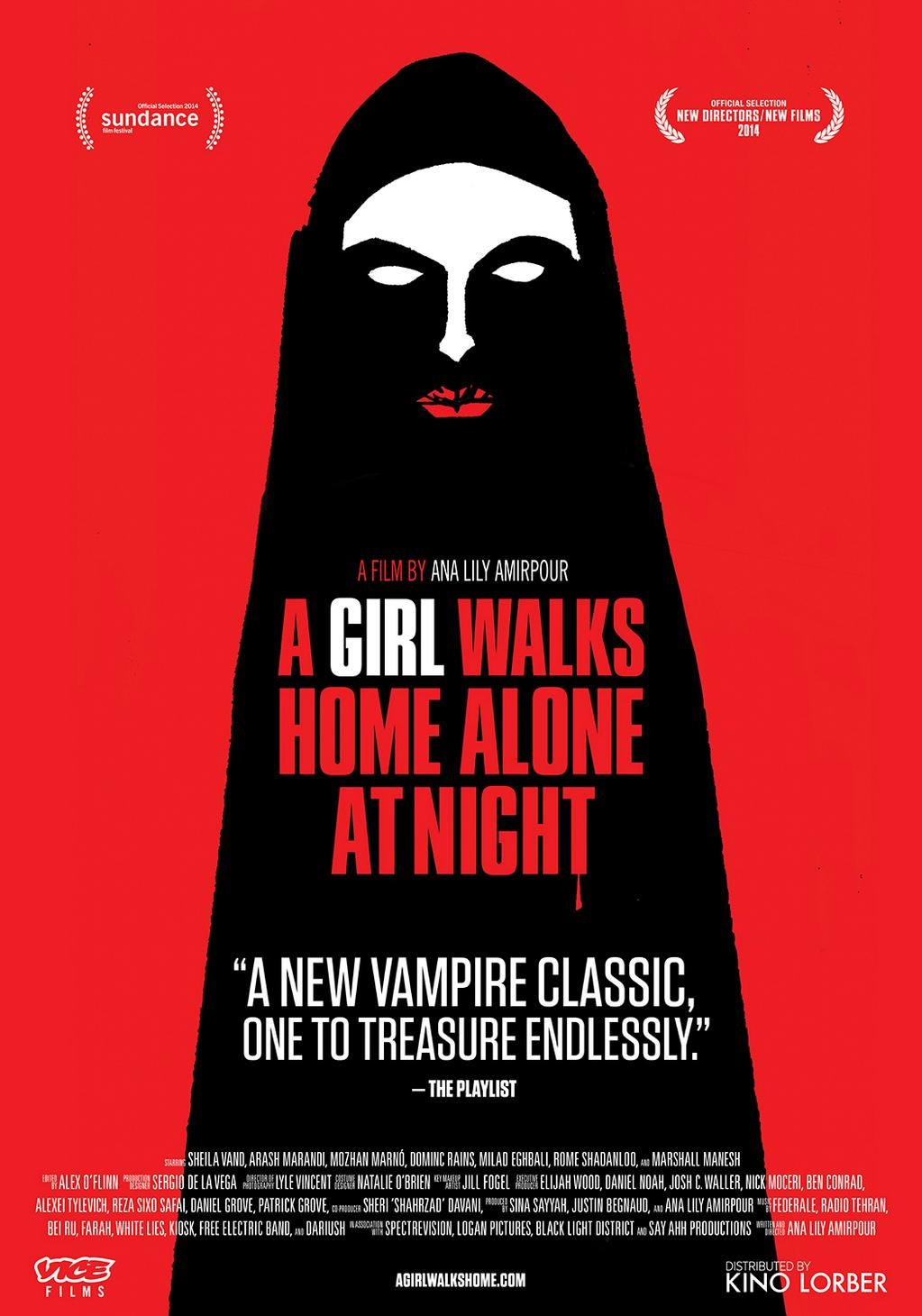

Film Review: A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014)

I’m reluctantly coming to terms with a hard truth: I like vampire movies. There’s no reason for me to be reluctant about it or any reason it should be hard, but it’s nagging me. I used to say that what I didn’t like was all the Victorian lace collars and brooding pretty boy Lotharios, but I don’t think I even mind that anymore. Those aspects are campy, no doubt, but I’ve never minded camp, so there goes my whole argument. However, even with this realization, in comparison, what I really like is unique vampire stories—ones that, while still grounded in accepted vampire lore, subvert tradition and bring something new to the table. That’s what Ana Lily Amirpour has done with her debut feature, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night. With just the right combination of humor, creeps, and atmosphere, she’s created something we’ve never seen in a vampire movie before while managing to keep it wholly within the realm of familiarity. It’s a feat.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is void of pomp and circumstance. Its black and white presentation by its very nature eliminates red flowing blood and flushed lover’s cheeks. What’s left is a stark contrast, allowing for plenty of pale anemia and shadow. Its vampire is no genteel aristocrat or reclusive lord. She’s a young woman who enjoys listening to records in her apartment. At night she dawns her long black chador and prowls the streets on a skateboard. She is a bat in human form, wings fluttering against the streetlights. It’s nearly irresistible.

The film’s setting of Bad City, Iran (real-life Taft, California) is a wasteland of oil drills, drugs, and prostitutes. It’s a western boom-town gone to pot. Nobody seems to notice or care what goes on in the shadows, and if they do notice, they sure aren’t talking about it. It’s the sort of town where missing persons are commonplace. There is a strange sort of justice at play, however, in the form of The Girl on a skateboard (Sheila Vand). Not content to be just a vampire, she’s a sort of vigilante as well—a rider on a pale horse, if you will. When she inadvertently comes to the aid of Arash (Arash Marandi) on more than one occasion, a bond is formed and her loneliness is given a reprieve.

Amirpour tackles this premise with a style that mixes the idiosyncrasy of Jarmusch with the pacing of Lynch. The world she’s created is familiar but skewed just enough to make it fantastic. It’s easy to recognize the town and landscapes pictured, but an air of unreality hovers over it—like the laws of nature are slightly different in Bad City, or that time doesn’t move as it should. Offbeat and archetypal characters are part of it, but Amirpour’s direction is what really pushes this feeling that this place plays by its own rules. She’s not afraid to let a scene linger or to make her audience slightly uncomfortable or unnerved. In fact, my favorite scene of the film is nearly five minutes of Arash and The Girl slowly approaching each other while a disco ball insanely spins, engulfing the room in hundreds of fireflies, with the darkest pop song since Joy Division on the stereo. It’s a beautiful, heartwarming, and intense scene, made better by Arash being dressed as Dracula and The Girl tending to eat people. There are several genuinely creepy moments in the film, but it’s this one that sets it apart from all other vampire stories. It’s all right there in tension and oddity of that room.

Not a lot happens. There’s no moralizing or metaphor—just a black and white sense of justice and an urge to feel something with someone. It’s that last part that gives A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night its most common ground with other vampire films, and what provides its biggest difference. Sure, there’s bloodsucking, darkness, and death by pointy teeth, but vampire movies (good ones anyway) are mostly about loneliness. It’s the possibility of losing this loneliness that sets A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night apart from its contemporaries. Vampires don’t always have to be doomed.