The Importance of Post-War Film Movements

Since the early days of motion pictures in the late 1800s, advances have been continually made around the world to improve the medium. At first, these advances were generally of a mechanical nature. Inventors, tinkerers, artists, and hobbyists alike were all working hard to make the motion pictures camera look and operate better. Some sought theses advancements to improve their art, seeing this new technology as an exciting way to entertain as well as create. Others saw it as a way to make a profit and were less concerned with its artistic capabilities. However, the medium of motion pictures wouldn’t have survived without the collaboration of both camps, which is something that is still true today.

When it comes to the movies, art and commerce go hand in hand. Film movements were born out of the merging of these two motivations. Add to this the need for a nation and a people to re-identify themselves in a post-war environment and some of the most important and influential film movements in cinema’s history are born. Post-war filmmaking movements are an opportunity for a nation to reinvent and reassert themselves after years of conflict, and the results have historically changed the way we look at cinema.

The generally accepted definition of a film movement is a group of films and filmmakers who have produced works that are in a similar style over a relatively small period of time, and are from the same region geographically. They often spring up as a reaction to some sort of political upheavals, such as recent, or ongoing war. The new governments of countries who have been on the losing side of these wars find themselves with a ruined landscape and a demoralized people. They often turn to the film industry to, not only reinvent their nation’s image that is presented to the world but to also uplift its people. A sort of renaissance happens after war has ruined a country, and cinema is one of the most powerful mediums that can be employed to regain a national identity. Let’s look briefly at two countries whose film industries were instrumental in rebuilding during post-war eras.

Germany

After Germany’s defeat in World War I (1914-1918), the country was in ruins, and the government turned to the film industry to re-invent its image. What resulted was the UFA, or Universum-Film AG, a subsidized national organization designed to put Germany back on the map. The filmmakers that the UFA attracted weren’t very interested in how movies had been made up until that time. Instead, they began experimenting with a much more avant-garde style. The free nature of this cinematic form gave the filmmakers an open canvas for expressing how the people of Germany were feeling at the time.

German Expressionism, as it came to be known, gave voice to the cynicism, alienation, and disillusionment that much of the country was feeling at the time. These films often focused on the inner turmoil of their protagonist, forcing the viewer into the mind rather than depicting the natural world. Strange camera angles, sharply angular sets, the clever use of shadows and light, and flawed, possibly insane or villainous protagonists are all benchmarks of German Expressionism. Titles such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), and Nosferatu (1922) gave birth to the horror genre, while Metropolis (1927) is an early foray into modern science fiction, influencing that genre to this day.

When Hitler rose to power in 1933, he saw these films as dangerous to his agenda due to their free-thinking nature. He seized control of the UFA, forcing many of its filmmakers to flee to the United States, where they became a huge influence on how Hollywood made movies. When these German filmmakers applied their techniques to American movies, their flawed heroes, and use of strong shadow gave birth to one of Hollywood’s most successful genres, Film Noir. The classic Hollywood hard-boiled detective would never have become the recognizable anti-hero we know him as today without the contributions of German Expressionist filmmakers such as Fitz Lang, Robert Wiene, F.W. Murnau, and G.W. Pabst among others.

Japan

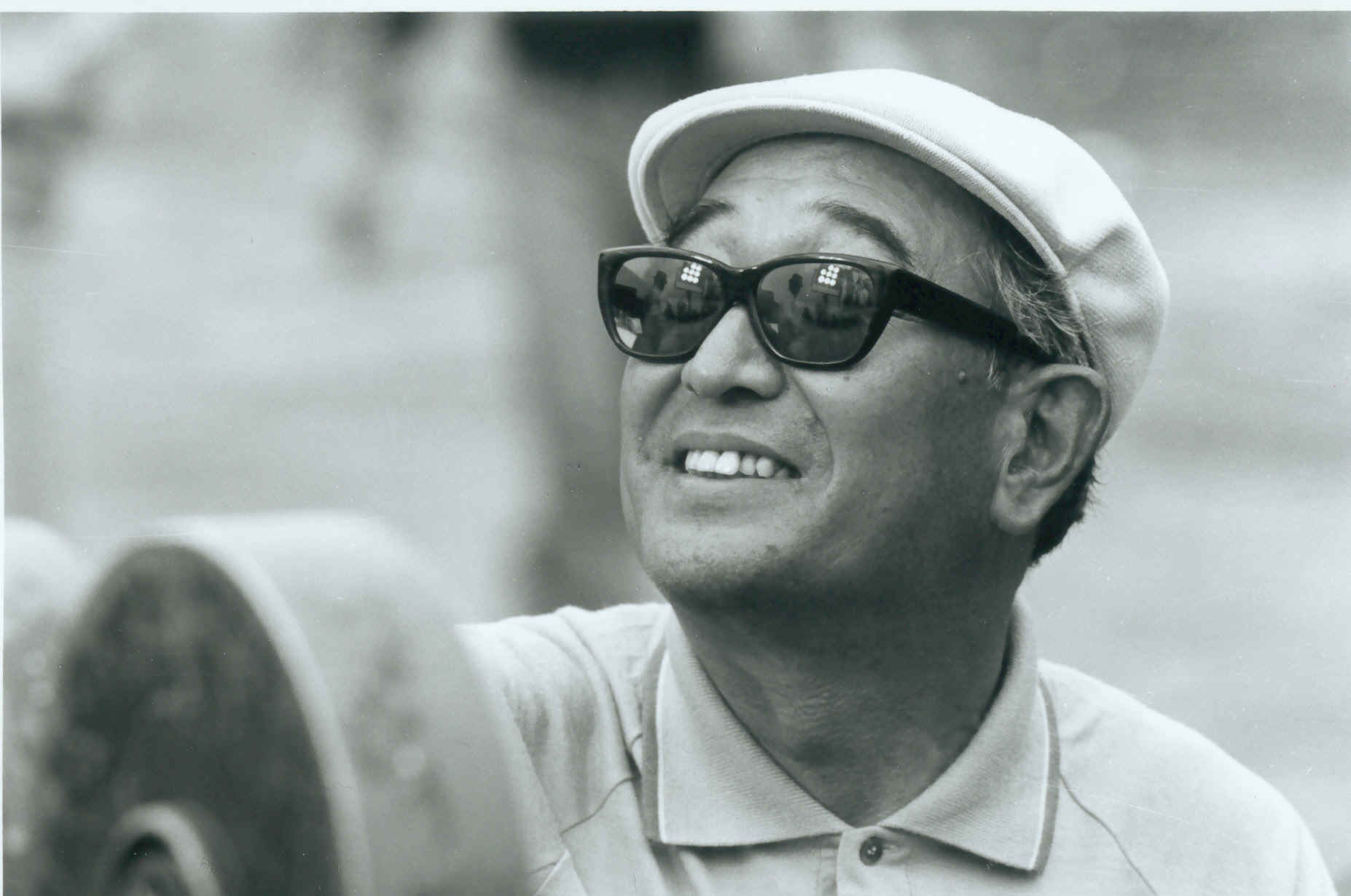

Another country that saw its film industry revitalized and gain international attention at war’s end, this time World War II, was Japan. Two important, but very different filmmakers come to mind when discussing Japanese post-war filmmaking. They are Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu. As in Germany at the end of World War I, the Japanese film industry was eager to rebuild itself after the war. Because the island was occupied by Allied forces, its filmmakers were heavily influenced by Americans such as John Ford, Howard Hawkes, and Orson Welles.

Kurosawa embraced these directors, making epic films styled after American “westerns”, replacing the American West with feudal Japan, and gunfights with sword battles. Although influenced by Hollywood filmmaking style, Kurosawa’s movies were very much a critique on Japanese culture. For example, in Kurosawa’s 1956 classic, Seven Samurai, individualism, or Western ideals, are represented through the flawed hero samurai, acting alone or in a small group to achieve their goals. On the other hand, the very Japanese notion of conformity, tradition, and working together as a unit is represented by the villagers, who work en masse.

Ozu critiques Japanese culture in a much more subdued way. Instead of epic landscapes, swordplay, and action, he uses subtle dialogue, static camera placement, and an editing style that places feeling over continuity to draw his viewers in. His films, such as his masterpiece Tokyo Story (1953), are also set in, what was at the time, the modern and middle-class Japanese home. He created microcosms of everyday Japanese culture, depicting seemingly mundane and simple stories with an extreme amount of emotional depth. He used the traditional family to express the truths, hopes, and disappointments of the modern, working-class people of Japan.

Ozu’s films are small when compared to Kurosawa’s, but their impact is just as great. Both filmmakers showed those outside of their native country that it was possible for art to critique life and that there are many different ways to express that.

Film movements come and go. In fact, most aren’t even recognized until they are already over. Only through analysis and criticism after the fact can their influence be recognized and acknowledged. They are often a representation of the mood of a nation at a particular time in history. They have their finger on the pulse of a culture and attempt to make sense of what is going on around them. Not all film movements are influenced by war and its aftermath, but many of the most influential are. These post-war film movements are part of a healing process for nations of people, as well as a statement to the rest of the world that says “we exist.”