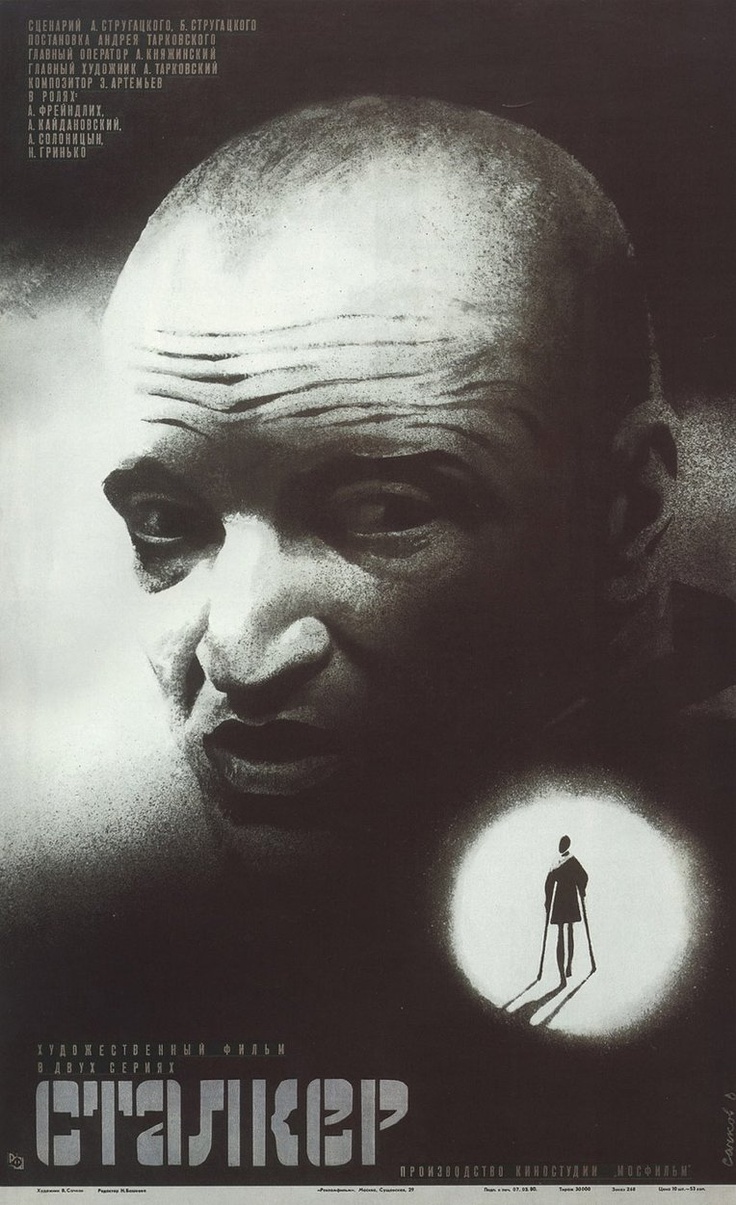

Film Review: Stalker (1979)

In an unspecified country, in an unspecified future, and created by unspecified means, there lies an area known as The Zone. No one knows for sure how The Zone came to be, but theories include a meteor strike, or possibly by more other-worldly means. It is also off-limits, guarded by soldiers with machine guns, and cordoned off with walls and fences topped with barbed wire. The only way in is to sneak with the aid of a Stalker—a professional guide and expert on all things Zone. Once inside, the laws of nature don’t quite apply correctly, and extreme caution must be taken to reach one’s destination—a mysterious place in the heart of the zone known as The Room. It is said that The Room can grant one’s innermost desires.

The Stalker (Alexander Kaidanovsky) leads two men, known only as The Writer (Anatoli Solonitsyn) and The Professor (Nikolai Grinko), into The Zone, and to The Room. All three travelers have their own stated reasons for wanting to enter (or not to enter) The Room, and their own private, secret reasons as well. Along the way, the trio discuss and argue these reasons while navigating the ruins and countryside of The Zone.

It is also implied that The Zone is at least partly sentient, setting ever-changing traps for any human visitor. Only a Stalker—possessing some sort of psychic compass—can safely navigate through these traps and pitfalls. It is known that not everybody makes it out of the Zone alive, but the risk is apparently deemed worth it.

The plot is deceptively simple, but the execution is nothing short of beautiful. Tarkovsky’s Zone resembles the ruins of a semi-modern civilization. Rusted firearms, bits of coin, and religious paraphernalia litter the shallow puddles and streams the men must slog through. Had Stalker been made today, and in Hollywood, The Zone, no doubt, would have had a distinctly “Sci-Fi” look—weird CGI creatures, unnatural colors, etc. Not so with Tarkovsky’s late 70s Russian production. It looks exactly like what the abandoned Russian countryside and factories looked like at the time because that’s where most of the film was shot. Its outward betrays its inward.

Stalker moves slowly, but don’t let that deter you. Tarkovsky’s long takes and long pieces of dialogue are offset by even longer periods of silence. These moments allow us to take it all in. We watch as the camera follows our protagonists to each new area of The Zone with long breathes of stoic movement. There’s no flash, per se, but when each scene is composed with such care, there doesn’t need to be. The long bits of dialogue compliment the long takes effortlessly, playing more like the chapters of a book than scenes of a movie.

It may play like the chapters of a book, but it’s composed like a painting. Tarkovsky’s eye is unmatched. He manages to capture the surreal and real of The Zone with great care and familiarity. The camera is often placed far away from the speakers, letting the whole screen breathe with life, even when there is very little happening. The smallest amount of movement (the trickle of a stream here, the wind through some leaves there) offers a level of tension that isn’t warranted for a film that’s paced the way this one is. The Zone is a mysterious place, and as the Stalker tells us over and over, regular rules of physics don’t apply there. Why can’t the rustle of some leaves be cause for concern, therefore tension for us? Such simple matters could mean the difference between life and death.

So, what is the film about? What does it mean? A film full of this amount of symbolism coupled with lengthy discussions on philosophy, art, religion, war, and the meaning of life must mean something, right? Well, here’s what Tarkovsky himself had to say about it in his book, Sculpting in Time:

“The Zone doesn’t symbolise anything, any more than anything else does in my films: the zone is a zone, it’s life, and as he makes his way across it a man may break down or he may come through.”

I don’t quite buy that, but the film’s protagonists offer so many varying and disagreeing view and opinions, who’s to say which ones the filmmaker held. What is so interesting about the philosophies discussed, is that it allows each viewer to make of it what they will. And it’s not just the dialogue that is easily dissected, consumed, and debated. It’s the sets, the props, the clothing, the rain, the running water, the grass, the alcohol, and on and on and on. Tarkovsky openly invites you to analyze every minute detail you see on the screen and then tells you that they mean nothing and that you’re wasting your time. That you should just enjoy the movie. I love it! What madness!

Stalker is an amazing piece of cinema. It’s a true gem. It has no special effects to speak of. It has no alien creatures. It has no big explosions. It’s missing a lot what you might expect to find in a Science Fiction film. What it does have is much more valuable. It has story, character, and most importantly, it has ideas. The actors, every single one of them, are exemplary, and they drive the film beautifully to its magnificent conclusion.

And what of the conclusion? I won’t give spoilers, of course, but it’s had me thinking for days (and likely for many more viewings). At the end of the film, when the credits roll, if your anything like me and feel the need to analyze every detail, you won’t be able to get this question out of your head: Why didn’t the glass break? I need to know, but of course, I never will, and it’s just one of the many nuances and detailed storytelling elements that makes Stalker so amazing. Like said earlier, it’s absolutely maddening, and I love it.