One Punk’s Guide to Professional Wrestling: PART TWO

The Carnies, The Hookers, and The Gamblers

Modern professional wrestling’s roots go back nearly as far as humankind, but the short branch on the long family tree of wrestling that spawned what we know today as professional wrestling can be traced back to 1870s England. Catch-as-catch-can style was a system of wrestling that encouraged combatants to incorporate any and all holds and moves into their repertoire to best opponents. It was brutal, and these athletes or hookers (named for the secret submission holds or “hooks” they used to end matches quickly), seemed to truly enjoy hurting each other. This no-holds-barred approach was both a very popular style to watch and an unpredictable style to combat. This new form of entertainment was an instant hit on the carnival circuit

In exchange for a cash prize, local tough men were encouraged to defeat these “hookers” as part of the carnival’s “athletic show.” They rarely succeeded and were often left battered, bruised, or worse. Many wrestlers eked out a living making side bets with locals, displaying the first cracks in historically recognized legitimate acts of athletic showmanship.

Out of this system rose some of wrestling’s original superstars, most notably, Frank Gotch and George Hackenschmidt, two legitimate tough guys with real wrestling talent. The popularity Gotch, a small-town kid from Humboldt, Iowa, and “The Russian Lion” developed became one of the best rivalries in the history of the sport. Their second of only two meetings drew over 30,000 fans to Chicago’s Comiskey Park in 1911, cementing their names in the history books.

While Gotch, Hackenshcmidt, and others were busy keeping traditional Greco-Roman and Catch wrestling in the headlines, another school was emerging. On the carnival circuit, gambling was often involved in the athletic shows, and thus began the shift from honest matches to less-than-honest ones.

Carnival owners and bookers began encouraging wrestlers to dress in lavish costumes and invent impressive backstories to enhance their appeal. While athletic talent was still a must, showmanship and spectacle grew in importance. Gambling was always rampant in wrestling, but since bookers and wrestlers were staging bouts, secrecy became of utmost importance if they expected to continue making money.

To be able to speak openly about the staged nature of the events without anyone else knowing, they developed a secret language. Kayfabe, as it came to be known, is still used today, albeit mostly as a recognition of tradition rather than any useful secret code. Using Kayfabe, the bookers, carnies, and wrestlers could discuss plans of milking their marks right in front of them. Conning hayseeds out of their hard-earned cash was the name of the game.

Legitimate wrestlers, or “shooters,” were becoming less common, and with Frank Gotch’s retirement from wrestling in 1913—and with no real star to take his place—fixed and predetermined matches became the norm. To the carnie’s dismay, however, spectators wanted what they were no longer providing. The con-men found themselves amid a backlash. The hayseeds weren’t having it anymore. Fans wanted to see legitimate tough guys hurt each other, not flamboyant showmen whom they suspected were on the take. Add that to the languid pacing of the scripted matches and you had fans leaving in droves. Wrestling’s popularity plummeted, and by 1920, something had to be done.

Toots Mondt and Slam Bang Western Style Wrestling

A spark was lit in 1919 that changed the face of professional wrestling forever. Three men formed an organization that provided the basis for how the business is run to this day. The Gold Dust Trio consisted of Ed “Strangler” Lewis (the era’s most recognizable star and champion), his manager Billy Sandow, and the real genius behind the operation and former carnival wrestler Toots Mondt. The changes and innovations Mondt implemented are the cornerstone of modern professional wrestling and have remained largely unchanged for nearly a century.

Debuting in 1912 to very little fanfare, Mondt, a miner’s son, refused to follow in his father’s footsteps. Determined to make it in the wrestling business, he was eventually taught the art of hooking, a skill that proved very useful down the line.

With wrestling crowds at an all-time low, Mondt knew something had to change if anyone was ever going to make any real money. In 1919, after joining forces with Lewis and Sandow, Mondt hatched a plan to bring fans back on a regular, paying basis. He called it “Slam Bang Western Style Wrestling.” It was a mix of traditional Greco-Roman, Catch, and freestyle wrestling, along with elements of boxing and old-fashioned lumberjack-style brawling. It was fast-paced, exciting, and, for the most part, what we still watch today. Within six months, it had changed professional wrestling forever.

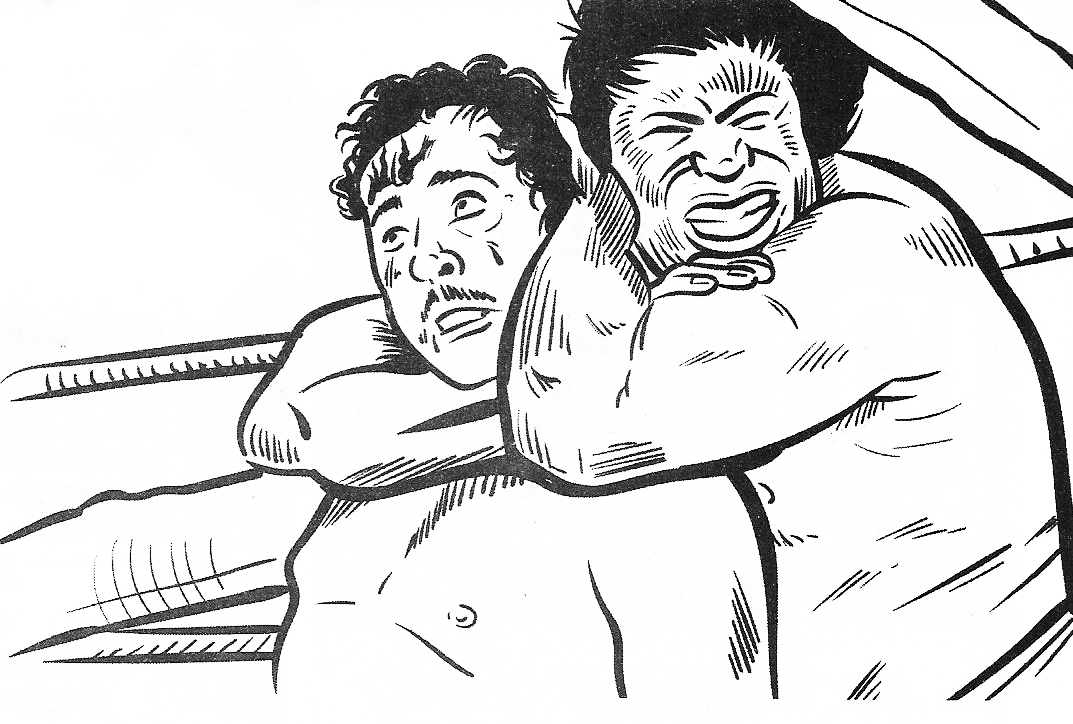

Wrestlers had so much more to do in the ring. Under the rules of Slam Bang Western Style, body slams, aerial maneuvers, and fisticuffs were not only allowed but encouraged. The action spilled out of the ring and onto the floor. It was a wild and bloody form of entertainment, and the masses bought it hook, line, and sinker.

While many matches in the previous decades had been fixed for gambling purposes, Mondt created—and convinced Lewis and Sandow to go along with—the idea of the “finish,” a predetermined ending that would entice the crowd to come back to see more. Count-outs, double-count-outs, and time-limit draws were amazingly effective ways to lure fans into coming back for rematches—not to mention the dozens of “submission holds” and other finishing moves Mondt invented to wow the fans. Gone were the days of gambling on fixed bouts, as the trio decided that the price of admission was how they were going to make their money. Gambling was strictly forbidden among wrestlers and promoters, giving a false legitimacy to a sport that had never been more scripted.

Lewis was the obvious choice for World’s Champion, but Mondt and the gang knew fans would eventually grow tired of the same face on the top of every card, so it was decided that, from time to time, Lewis would lose his title, or “put over” another wrestler. This insignificant notion by today’s standards was revolutionary in 1919. This became known as “working a program,” or developing an ongoing storyline to keep fans interested, and was integral to success in this new way of doing business. No one would ever believe that “The Strangler” would lose on purpose, but for match after match to have significance, he had to be shown as vulnerable. This setup, of course, led to rematches in which Lewis regained his title in a glorious comeback of epic proportions and record gate receipts, of course.

In the 1920s, the trio were the guys you wanted to work for. Wrestlers flocked to their stable because, unlike any other promoter up to this point, with The Gold Dust Trio, you received a regular paycheck. This was another innovation, and a necessary one. Without regular pay, there was nothing to stop a disgruntled wrestler from going to the public about the scripted nature of the matches. Everyone got paid, everyone played along protecting the business and its secrets, and everyone was happy and fed.

The trio developed a centralized promotion, handling bookings all over the country. They lured talent away from almost every carnival and small-time circuit. A hierarchy of talent was established, with Lewis on top. Those with enough legitimate talent were permitted to work programs with him and were pushed to the top tier. Those who might have less talent but were entertaining in other ways were kept on the mid or lower cards.

Wrestlers who weren’t considered “American” enough—either by surname, first language, or color—were rarely allowed to challenge for the World’s Championship and were often kept on the lower tiers, unless working territories with large immigrant populations that shared that ethnicity. Mondt and the gang knew how to work the crowd, and they used every means at their disposal—race included—to bring them in.

Race has always been an issue in professional wrestling. The very nature of heels versus babyfaces is that one of them (the heel), is generally some form of “other.” This otherness, from the early carnival days, up to and including right here and now, often refers to race or country of origin. Promoters, from day one, knew that using race to get heat (a reaction from the crowd, generally cheers and encouragement for babyfaces, and boos and resentment for heels) would keep the seats filled and the gate receipts high. Using the crowd’s built-in prejudices was an extremely effective way to generate a draw.

In the years following WWII, the obvious go-tos were Germans, Russians, and Japanese. Sometimes these wrestlers were legitimately from these countries, but often, their gimmicked ethnicity was nothing more than a well-crafted “work” (a scripted aspect of the storyline, as opposed to a “shoot,” which is a real-life aspect). Cartoonish Germans and Russians were occasionally given heel title runs, but these were simply a ploy for the triumphant, white, all-American to win it back in a spectacular fashion.

The ’70s ushered in an anti-Arab sentiment, which made stars like The Iron Sheik (real-life Iranian, Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri) one of the most famous heels of all time. Native American wrestlers were also heavily racialized through the years, although often as babyfaces. Many of these wrestlers were of questionable heritage, but even with that, what may have been meant as flattery of culture (decorative headdresses, ceremonial dances, et cetera), ended up, especially in hindsight, appearing as mockery at best. Exploitation is a more accurate description.

In 2003, Triple H (Paul Levesque) cut a promo (an on-air speech meant to rile the crowd and build heat for an upcoming match) on African American star Booker T that summed up the wrestling business’ policy towards black wrestlers. He said, “Somebody like you doesn’t get to be a world champion.” A work to get heat? Maybe, but history backs up his words.

Black wrestlers have been a staple of professional wrestling dating back to, at least, the 1870s (a wrestler named Viro Small often gets the credit for being the first verifiable African American pro wrestler, making his debut in 1870). Like professional baseball, wrestling also had black-only promotions. Stars of these territories were considered by many to be among the best in the world but were only allowed into white promotions when the proper heat was needed. Lou Thesz, in his book, Hooker, had this to say about ’50s and ’60s African American star, Luther Lindsay: “Like many other industries, wrestling was not open to African-American wrestlers during his career, so it was an amazing accomplishment for Luther to even learn his craft. His place in history is not because he was black; it is in spite of the fact he was black.”

Lindsay and many others, such as Bobo Brazil were trailblazers for black wrestlers to come. In 1962, Brazil defeated “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers for the NWA championship (a first for an African American). Through a series of contrivances, however, the NWA board did not recognize the title change. Ron Simmons was the next black wrestler to win a major championship in a white-owned promotion, but it wasn’t until 1992, a full thirty years later.

The Rock (Dwayne Johnson, half black, half Samoan) has had numerous title runs and is, by far, the most successful non-white wrestler in history. Combine this with Booker T’s championship win in 2000, and you have a few very clear exceptions that prove the rule. Triple H’s words about Booker T have remained largely true.

This lack of title recognition isn’t the only factor in wrestling’s often racist history. A quick survey of the gimmicks given to non-white wrestlers is an embarrassment. Flamboyant characters are common within the squared circle, but for wrestlers with non-European heritage, this flamboyance is often played out as blatant racial stereotyping. Gang members and thugs for blacks, esés or matadors for Latinos, and cartoonish martial artists for Asians. For white wrestlers, the ethnicity of their opponent is fair game when cutting promos, often sinking to embarrassing depths.

Latino, Asian, and Samoan wrestlers have fared slightly better than African Americans when it comes to championship representation—Giant Baba, Pedro Morales, Yokozuna, Eddie Guerrero, Rey Mysterio, Alberto del Rio, The Rock, among others, have all worn the belt, but have all done plenty of time as racially stereotyped heels as well. For many, these gimmicks are the only ones they’ve ever had on U.S. soil. Historically, in the United States, non-white wrestlers are often nothing more than an “other” for the white wrestlers to defeat.

Back to the Goldust Trio.

From time to time, a wrestler might get upset about his spot in the food chain. Maybe he thought he should be pushed higher on the card. Maybe he thought he should be the champ and not “The Strangler.” On the rare occasion a wrestler got out of line, threatened to expose the business, or refused to go along with the “work” and the “program,” his next bout would be with the original enforcer himself, Toots Mondt.

Mondt was such a good hooker that he was legitimately feared throughout the business. If you found yourself in the ring with Mondt, you were made to realize very quickly that you had better rethink your actions. He had no qualms about leaving you a broken, bloody mess. This genuine fear of Mondt and the fact that everyone was making more money than ever kept most mouths shut. Mondt rarely had to act in his role as enforcer.

The wrestling business had its origins in legitimate violence. While under Mondt’s tutelage, the match finishes may have been decided in advance, but this did nothing to curb the very real violence that still took place. Until at least the 1980s and the rise of WWF’s family-oriented packaging, the business of professional wrestling remained extremely bloody. Legitimate chops, punches (known as “potatoes,” and often came with an angry “receipt”), kicks, and bone-breaking holds were very much the norm. Seeing a wrestler bleed profusely was not only common but expected. Freely flowing blood was one of the ways to maintain the legitimacy of the sport. You had to keep up appearances.

Next week, the introduction of television changes the business forever!

PART ONE / PART TWO / PART THREE / PART FOUR / PART FIVE

Originally published by RAZORCAKE MAGAZINE.