One Punk’s Guide to Professional Wrestling: PART THREE

Television and the Territories

The Gold Dust Trio disbanded in 1928, but the style of wrestling they popularized stayed intact. Strangler Lewis remained an active title holder and contender into the 1940s, but with the Gold Dust Trio no longer active as a booking entity, many wrestlers and promoters saw the need for another organized central office to oversee things. It took some time, but in 1948, a group of promoters from around the U.S. got together and formed what became the dominant force in professional wrestling for the next thirty years.

The National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) could not have come along at a better time. Television, still in its infancy, embraced professional wrestling from day one. The larger-than-life characters, melodramatic storylines, and physical violence were perfect for the new medium. Television and wrestling were tailor-made for each other, and they used each other to make a lot of money.

Early television stars like Gorgeous George used this new platform to become household names. Not the world’s greatest athlete, Gorgeous George more than made up for this with his exciting showmanship. With his bleached blonde hair, entrance music, lavish robes, and hoity-toity air, Gorgeous George brought a spectacle to wrestling, and to television, the likes of which no one had ever seen. He was pro wrestling’s first true villain. He cheated at every opportunity, insulted the crowd, and ran from the babyface whenever things didn’t go his way. Gorgeous George had the unique ability to make everyone in the world hate him just by strolling to the ring. What he did in his time was the model for all the best heels to come, and many of the babyfaces too. He was also the first face of one of wrestling’s other popular ways to get heat: homophobia.

As with its race issues, wrestling’s historic attitude toward LGBTQ communities is largely mirrored by society. It’s a bigger picture issue that often gets played out in a wrestling ring, with thousands of fans, sadly, cheering it on. Gorgeous George’s gimmick was that of an effeminate, prim and proper aristocrat. To the television viewers of the 1950s, he may as well have been a Martian. “How could a man act like that?” they wondered.

Effeminate-acting wrestlers continued riling up crowds for decades. In the mid-’80s, veteran wrestler, Adrian Adonis, adopted a “gay” gimmick that was met by the ire of Roddy Piper, who, as the babyface, basically gay-bashed him into oblivion. This wasn’t Piper’s only homophobic program. In 1996, Dustin Rhodes began using his now much watered-down androgynous gay panic character, Goldust, to get under the skin of Piper. In true ignorant fashion, the WWF brass had Goldust repeatedly come on to Piper over the course of several weeks, culminating in what was essentially a televised hate crime.

Adonis and Goldust are the short list of wrestlers posing as gay to gain heat. In the 2000s, tag teams such as Lenny and Lodi, and later Billy and Chuck were portrayed as gay couples in an attempt to stir up some heat. They caught the eye of the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), which said that they were “…presented with the intention to incite the crowd to the most base homophobic behavior.” They were absolutely right. Wrestling crowds roundly exposed themselves as intolerant homophobes.

The strangest thing about homophobia in the wrestling business is simply, especially since the 1980s or so, how homoerotic the whole thing really is. Fans to this day see no issue with admiring and cheering for “Ravishing” Rick Rude or “Mr. Ass” Billy Gunn, glorified male strippers who oozed homoeroticism. One of wrestling’s most popular bad boys of all time, Shawn Michaels, of DX and The Rockers fame, even posed nude for Playgirl, for chrissakes. The disconnect is staggering.

To the wrestling world, homophobia was just another way to get heat, an added “other” to be exploited and manipulated, but most gay performers have had to keep the secret of their non-gimmick, real-life homosexuality a secret from the business.

There have been some, such as Pat Patterson, who have been lucky enough to be accepted as gay since the ’70s, albeit never acknowledged on television. Patterson’s homosexuality remained an open secret until 2014 when he officially came out on an episode of WWE’s Legends’ House (with Roddy Piper in attendance, of all people).

Others, though, such as Chris Kanyon, were forced to keep their mouths shut out of fear of reprisal. Wrestling writer, Dave Meltzer said of Kanyon: “He kept his homosexuality secret, but it tore him up when other wrestlers would, in front of him, talk about how much they hated gays or made gay jokes.” Chris Kanyon committed suicide in 2010.

While still struggling with its homophobia issues, the WWE, on its surface, appears to be making strides. In 2013, for the first time, an active roster member, Darren Young, came out as gay. The WWE released an official statement supporting Young, with many fellow wrestlers tweeting their support as well.

Meanwhile, back in the 1950s, the U.S., Japan, and Mexico were carved up into territories, each run by a different NWA board member. These bosses had a mafia-like understanding that no other promoter would run shows in another’s territory unless special arrangements were made. Talent pools would no longer be raided, but deals were often struck to trade or loan talent if a wrestler was unhappy or if a storyline or program might benefit from fresh faces. If a rival non-NWA promotion opened up shop, the bosses would band together to shut it down. Intimidation and threats of violence against rogue promotions were common tactics. Not playing the game was no longer an option by the 1950s.

The NWA named Orville Brown as its first World Champion, but after an auto accident ended his career, the title was vacated and handed to his number one contender, a twenty-two-year-old named Lou Thesz. An accomplished hooker, Thesz was chosen for his ability to enforce the new rules on anyone who didn’t play along. If a wrestler didn’t lose to him when and how the NWA board told you to, they were going to get hurt. Thesz traveled the country, defeating regional champs, unifying the titles into one—the National Wrestling Alliance World Heavyweight Championship.

It was decided that the NWA champ would not belong to any one promotion. Instead, he would travel from territory to territory challenging that region’s top stars. Often, the buildup for these programs started a year in advance. Top heels were also sent around to the territories to run programs to sufficiently hype the toughness of the local talent. When the champ arrived, it was important fans believe their guy had a shot at the belt, even though title changes were decided by the territory bosses at annual NWA board meetings.

It was a good system, but cracks emerged. Not all the promoters liked being governed by a board. Within ten years, several promoters left the organization, most notably Verne Gagne in the upper Midwest and Vince McMahon Sr. in New England. Their respective organizations—the American Wrestling Association (AWA) and the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF)—became the most lucrative promotions outside of the NWA, and wound up giving them a real run for their money.

The ’60s and ’70s—Gagne and McMahon

By the end of the 1950s, most of the territories were hitting their stride. Many had settled into well-attended weekly or monthly shows, developed television deals, and cultivated the talent to draw fans to both. Those that failed at this quickly went out of business, only to be replaced by another upstart company. Business may have been down from earlier in the decade when television was just beginning to become a household commodity, but it was still steady enough to keep most companies open. Getting a program with the NWA champ once a year was just fine for most promoters, but not all. While many were content with their place in the NWA pecking order, there were some who saw a bigger picture. By the end of the 1970s, wrestling was hotter than ever, and big changes were just around the corner.

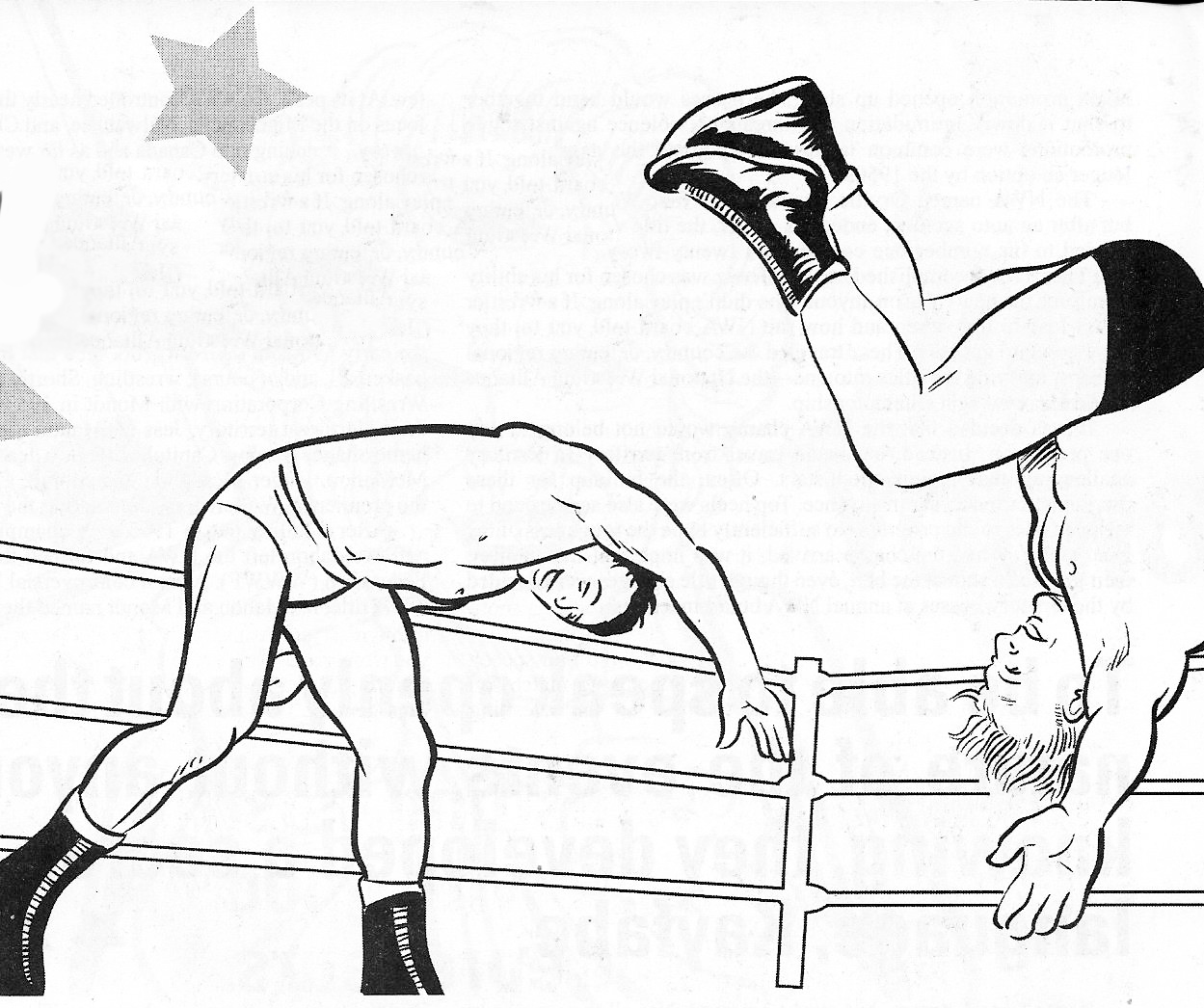

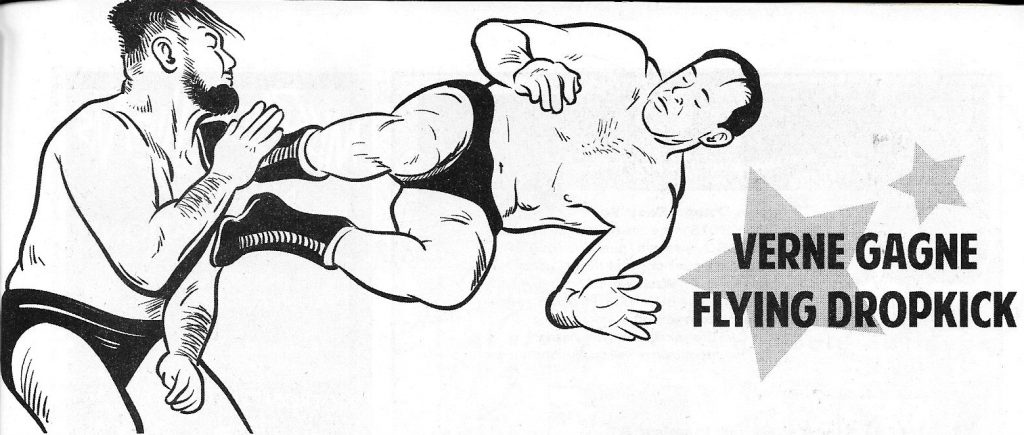

In Minnesota, by 1959 the territory had come into the possession of their charismatic star, Verne Gagne. A no-nonsense hooker, Gagne had made a name for himself in the 1950s wrestling on national television. He was a household name and one of the most successful wrestlers working in the business at the time. After a series of controversial title change decisions made by the NWA board, Gagne was denied a title run he felt he deserved. In 1960, he officially left the NWA, founding the American Wrestling Association (AWA).

Some of the world’s most famous wrestlers and personalities got their big breaks working for the AWA: Hulk Hogan, Jesse Ventura, Bobby Heenan, The Road Warriors, and Gene Okerlund, to name just a few. At its peak, the AWA controlled nearly the entire Midwest (with its focus on the Minneapolis, Milwaukee, and Chicago territories), as well as areas stretching into Canada and as far west as San Francisco.

The Northeast territories, centered in New York, had naturally always been a hotbed of wrestling activity. Many years after leaving the Gold Dust Trio, Toots Mondt made his mark on the wrestling business once more. This time around, he partnered with the first in a long line of promoters from the family whose name became synonymous with the industry: The McMahons. Roderick James “Jess” McMahon was the first. He began promoting sporting events in the early 1900s in the New York area that included boxing, baseball, basketball, and of course, wrestling. Shortly after founding the Capitol Wrestling Corporation with Mondt in 1953 and joining the NWA as their Northeast territory, Jess McMahon died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage, leaving Capitol without a leader. Enter Vincent James McMahon. Under McMahon and Mondt, Capitol Wrestling became the premiere NWA territory, dominating the group’s bookings.

After a falling out in 1963 over championship bookings, Mondt and McMahon left the NWA and formed the World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF). After a controversial loss to Lou Thesz for the NWA title, McMahon and Mondt named their top heel, “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers, as their first champion. The company had been formed so quickly that a WWWF Championship belt hadn’t even been made yet. When Rogers was announced on TV as the new champ, he simply wore his old NWA U.S. Championship belt, a title he still technically held. It wasn’t until a month or so later, when he dropped the title to Bruno Sammartino that a new belt was made specifically for the WWWF. Sammartino held the title for the next eight years, finally losing it to Ivan Koloff in 1971.

As the ’70s drew to a close, wrestling was more profitable than ever. As the world grew smaller, however, the old models weren’t going to work forever. The territory system, dating back to the 1920s, had worked largely unchanged for nearly sixty years, and many old-school promoters saw nothing wrong with it. It took a young, brash, third-generation promoter to change all of that forever.

Next week, a young hotshot hits the scene and immediately starts to stir things up. The business will never be the same!

PART ONE / PART TWO / PART THREE / PART FOUR / PART FIVE

Originally published by RAZORCAKE MAGAZINE.