One Punk Goes to the Movies: The Interconnected Worlds of “Pather Panchali” and “Roma”

One of the reasons I love international punk is because it makes me feel connected to a global scene. Whether or not I can understand the lyrics is irrelevant. The urgency and power of the music resonate because, like film, punk has a language that isn’t defined by words alone. Movement, tone, emotion, and visuals are all part of the equation, but there’s something further that connects it all together. Below the surface, themes start to emerge—themes that have no borders and no expiration dates.

There’s a reason Minor Threat or the Dead Kennedys are timeless. Their themes transcend decades (sometimes scarily so), but so do those of Mob 47, Dezerter, or The Stalin. Movies and directors act in much the same way. For every Steven Spielberg or Wes Anderson, there’s Ingmar Bergman, Paweł Pawlikowski, or Hiroshi Teshigahara attempting to convey the ups and downs of the human experience through stories played out over time on film. Like with punk, the details and presentation may vary, but the emotions behind them and the truths they attempt to convey often don’t. Both show us that, regardless of where we’re from or what language we speak, we’re all in this shit together.

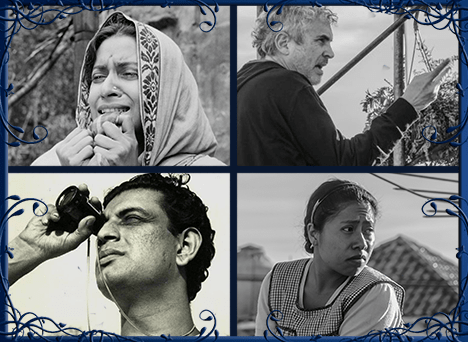

Two filmmakers who embody this notion are India’s Satyajit Ray and Mexico’s Alfonso Cuarón. Halfway around the world and over sixty years apart from each other, these two men each made a film that is both uniquely their own but thematically and emotionally connected. Both films deal with life during times of upheaval or change, with women as familial centers of strength in the face of absent fathers and the failures of men. Ray’s Pather Panchali (Song of the Little Road, released in 1955) and Cuarón’s Roma (2018) are two very different films made by two very different filmmakers, but the bonds that hold them together defy nationality and are relatable across cultural lines.

Satyajit Ray was born in Calcutta in 1921 into a long familial line of poets and artists. He began his career in 1943 as a graphic designer with a British-owned advertising firm. While he enjoyed the work, he took issue with British/Indian relations within the company (the British artists and executives earned more money). In the late ’40s, Ray and a handful of his artistically-minded friends founded the Calcutta Film Society. Not satisfied with strictly Indian cinema, the group sought out European and American films to screen. Ray, having become friends with several American G.I.s stationed in India during World War II, was kept abreast of all the latest American releases.

In 1949, Ray had the opportunity to meet and work with renowned French director Jean Renoir, who was in India shooting a film. With Renoir’s encouragement, Ray began to consider making his own movie. Then, in 1950, Ray’s agency sent him to London on an assignment where he reportedly saw ninety-nine films including Italian director Vittorio de Sica’s neorealist masterpiece, Bicycle Thieves. It was this film that finally convinced Ray to become a filmmaker. Lacking experience or training of any kind, Ray cobbled together a cast and crew and started production on his first film Pather Panchali (based on a popular children’s book) in 1952. It tells the story of young Durga (Uma Dasgupta) and Apu (Subir Banerjee), who grow up in the Bengal countryside with their parents (Kanu Banerjee and Karuna Banerjee) and elderly, dependent “Auntie” (Chunibala Devi). Apu is a dreamer while Durga is a realist and a handful. She continually tests her mother’s patience with her strong will and defiant attitude. Tensions mount as their father leaves for long periods of time in search of work.

Ray worked on Pather Panchali intermittently between 1952 and 1955. His non-existent budget only allowed for filming to take place when enough funds could be scraped up. This approach did, however, allow him to hone his craft over time. In essence, he became a better filmmaker as the production progressed—something many observers have claimed is evident in the final product. When Pather Panchali was released in India 1955 (under the title The Story of Apu and Durga), it wasn’t exactly a smashing success. Ray’s realist approach varied widely from the highly stylized commercial films of Calcutta’s film industry at the time and many audiences were confused by his technique. But, after screenings at Cannes in 1956 and in England and the U.S. a few years later, the legacy of Pather Panchali became cemented as a monumental work of Indian cinema both at home and abroad.

Alfonso Cuarón was born in Mexico City in 1961, nine years after Satyajit Ray began production on his first film. The son of a doctor and a biochemist, Cuarón was raised in an affluent neighborhood and showed an early interest in science. It soon became clear, however, that Cuarón was an artist. He studied philosophy and filmmaking in Mexico City universities and began making short films with fellow classmates and future frequent collaborators.

Success came early for Cuarón. By the mid-1990s he was directing feature films in the United States, including The Little Princess (1995) and Great Expectations (1998). However, it was his return to Mexico for his Spanish language film Y Tu Mamá También in 2001 that put Cuarón firmly on the map as a writer and director to watch. An international hit, Y Tu Mamá También was Cuarón’s first major attempt at a semi-autobiographical approach to storytelling. It wouldn’t be his last.

More successes followed. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004), Children of Men (2006, often considered one of the best science fiction films ever made), and Gravity (2010, for which Cuarón became the first Latin American filmmaker to win the Best Director Oscar) all helped solidify him as one of the preeminent filmmakers of the 21st century. In 2016, this prestige allowed him the freedom to begin work on a project of a more personal nature. The result was Roma, a film based on Cuarón’s upbringing in 1970s Mexico City, told through the eyes of Cleo, an indigenous maid based on Liboria “Libo” Rodríguez, the live-in nanny instrumental in raising the young artist. Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio, in her phenomenal debut) is loved by the family she works for but often goes unnoticed until she’s needed. She is warm and caring, but a commodity. Cleo is keenly aware of this dynamic, and the vanity of her employer (Marina de Tavira as Sofia, the children’s mother), but prefers it to life in the impoverished village of her birth.

These two films, Roma and Pather Panchali, are set fifty years apart from each other, take place on different continents, and concern families of varying social and economic status, yet are still connected by multiple threads of the same human experience. In rural Bengal in the 1920s, women are seen on rooftops doing the laundry. The same goes for servants in 1970s Mexico City. In the Indian countryside, impoverished children chase the sweets man in dashed hopes of a treat, while in the upscale neighborhoods of Mexico they vacation in the country and go to the movies. In both cases, it’s the women—whether as mothers or caregivers—who provide the structure, the discipline, and the moral compass of these two very different families. And in both cases, the children are oblivious to the turmoil inside these women.

Absent fathers is another common thread—albeit for different reasons. Roma’s patriarch (Fernando Grediaga) disappears near the beginning of the film. He says he’s off to a conference in Canada, but in truth he leaves to live with his mistress. In addition, after Cleo becomes pregnant, the father (Jorge Antonio Guerrero) disappears and threatens violence when confronted. In Pather Panchali, Harihar isn’t nearly so devious, but as an unsuccessful poet and playwright, he’s often away for long stretches at a time seeking work in other areas. Whatever the reasons, the women are left to care for the children on their own and with the help of other women. Their men have failed them, but they have no choice but to keep moving forward.

Each film takes special care to introduce us to the homes of these families to welcome us into their worlds. Interestingly, each also speaks of abandoned dreams and offers pretty on-the-nose gestures towards escape and exploration. In Roma, commercial airplanes are seen flying overhead, while the children of Pather Panchali are obsessed with catching a glimpse of a passing train. These examples of mass transit or migration also offer a hint at the coming modernization and potential upheaval of tradition and way of life. As we get to know the homes and surrounding areas of these films, their settings become rich tapestries to explore and savor. Ray and Cuarón both make sure we know these neighborhoods and villages so that we care what happens within them and are sad when they are gone.

There’s also a boiling chaos just under the surface in both films—one more pronounced than the other—but as modernization and the “old ways” become a thing of the past, change is inevitable. Whether this change comes from political unrest or simply the realization that things can’t stay the same forever, the women of Roma and Pather Panchali band together and persevere. Old grievances are put aside as new bonds are formed and new chapters are written. Of course, these realizations come at a cost. Tragedy inevitably strikes both families, forcing this new way of life onto each in their own way.

Pather Panchali was Ray’s first film of many—including the two sequels that make up what came to be known as “The Apu Trilogy.” He died in 1992 at the age of seventy with the well-deserved moniker “The Godfather of Indian Cinema.” He is a cultural icon in Calcutta and his legacy inspired fellow international filmmakers like Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman, as well as contemporary directors like Martin Scorsese and Christopher Nolan. His observation and treatment of the human experience are praised as peerless and his influence crosses all borders.

At fifty-seven, Alfonso Cuarón seems to be just getting started. He is now a multiple Academy Award winner, and in 2018, Roma made the top-ten list of nearly every critic in the world. In an astonishing pair of feats, these two artists, Ray and Cuarón—from different countries and different decades—somehow tapped into the same universal truths about men, women, and families that are both honest about the male psyche and surprisingly tuned in to the challenges faced by women and mothers, as well as caregivers and surrogates. Their films are beautiful, tragic, uplifting, and inspiring, but most of all they are sincere odes to the often overlooked, overworked, and underappreciated women in our lives.

Originally published by RAZORCAKE.