One Punk Goes to the Movies: Jean Seberg and COINTELPRO

It started with a small piece that ran in the celebrity gossip column of the Los Angeles Times. In May 1970, features editor Jim Bellows received a tip that seemed too good to pass up.

The tip read:

“I was just thinking about you and remembered I still owe you a favor. So I was in Paris last week and ran into Jean Seberg who was heavy with baby. I thought she and Romain had gotten together again but she confided the child belonged to [name deleted] of the Black Panthers. The dear girl is getting around. Anyway, I thought you might get a scoop on the others.”

Without substantiating or fact-checking the claim, Bellows passed it along to Joyce Haber, the paper’s rumor-mongering staff gossip columnist. The tip stated that the child Seberg was carrying was not Romain Gary’s (Jean’s on-again-off-again husband, a French author, diplomat, and movie director), but that of a prominent member of the Black Panther Party. The actress was white, the father—it was alleged—was black. Quite a scandal in 1970, especially considering that interracial marriage was against the law in the U.S. until 1967. Haber’s column, which ran on May 19 and was then reprinted in Newsweek and hundreds of syndicated newspapers, read:

“Let us call her Miss A, because she’s the current “A” topic of chatter among the “ins” of international show business circles. She is beautiful and she is blonde.

Miss A came to Hollywood some years ago with the tantalizing flavor of a basket of fresh-picked berries. The critics picked at her acting debut, and in time, a handsome European picked her for his wife. After they married, Miss A lived in semi-retirement from the U.S. movie scene. But recently she burst forth as the star of a multimillion dollar musical.

Meanwhile, the outgoing Miss A was pursuing a number of free-spirited causes, among them the black revolutions. She lives what she believed, which raised a few Establishment eyebrows: Not because her escorts were often blacks, but because they were black nationalists. And now, according to all those really “in” international sources, Topic A is the baby Miss A is expecting, and its father. Papa’s said to be a rather prominent Black Panther.”

Haber’s thinly veiled attempt at maintaining the actress’s anonymity was nothing more than a gimmick to further gossip. Everyone knew that it was Seberg she was referring to, and everyone bought into the story. Haber had no illusions about the damage a story like that could do to someone’s personal and professional life in 1970—and she didn’t care. The column was intentionally snide and mean-spirited, but that’s not all it was.

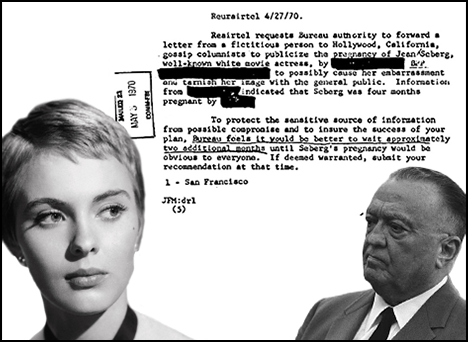

Joyce Haber’s column was the opening salvo in an FBI plot to destroy Jean Seberg’s credibility and reputation. It was the Bureau’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) who sent the original tip to Bellows, who either didn’t know or didn’t care that it was false. After the column was reprinted in Newsweek and gained national attention, the pregnant and fragile Seberg went into premature labor because of a suicide attempt from the stress put on her by the press. Her newborn daughter died two days later. In 1979, nine years after the incident, Seberg committed suicide in Paris. She was forty years old.

Jean Seberg was born in Marshalltown, Iowa in 1938 and had a nondescript life as a child. Her interest in acting led to her winning a nationwide talent search of eighteen thousand hopeful young actors. She was cast in Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan in 1956. Her performance was panned, but at just nineteen years old she was determined to make it as an actress.

After a few more flops and critical failures in the late ‘50s, Seberg found herself in Paris and on the radar of Jean-Luc Godard. Her breakthrough came in 1960 when she starred in Breathless, Goddard’s directorial debut. It was an international success, and would introduce the world to the “French New Wave” and to Seberg’s newfound confidence.

Seberg’s short-cropped hair and cool, detached attitude was all the rage among European youth, and it seemed for a time that she had finally found her calling in French cinema. However, still under contract with Columbia Pictures in Hollywood, Seberg traveled back and forth throughout the decade, making American and European films with varying degrees of acclaim and box office success—including the “multimillion dollar musical” Haber mentions (1969’s Paint Your Wagon, starring Lee Marvin and Clint Eastwood).

In the late ‘60s, Seberg, like many in Hollywood, found herself drawn to activism. She offered financial support to several causes including Native American schools near her hometown in Iowa, the NAACP, and the Black Panther Party. Her contributions caught the eye of the FBI and, again, like many in Hollywood, they opened a file on her and her activities.

The FBI’s COINTELPRO division was originally intended to weed out communists and fragment the ranks of the Communist Party USA in the 1950s. When the Civil Rights movement got underway with the forming of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), FBI director J. Edgar Hoover altered the program’s mission. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was an early target under this new direction. Internal memos about King state, “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro, and national security.”

When the FBI found that Jean was pregnant in late 1969, they seized on the opportunity to discredit her, thus nullifying any potential headway she or any other Hollywood liberals may have been making in Civil Rights causes, the anti-war movement, the women’s movement, or any other “New Left” arenas. The list of Americans the FBI was surveilling during this time is lengthy. Claims that the program also infiltrated far-right groups such as the KKK have since been proven false, meaning the only targets of consequence were left-leaning “subversives.” Often, surveillance and wiretaps were performed without warrants and were completely illegal.

COINTELPRO tactics differed from traditional investigation and prosecution in that the goal was to disrupt movements rather than arrest and prosecute criminals. Strategies mostly involved infiltration intending to sow dissent among members, thus fracturing organizational structures causing movements to fall apart at the seams. Another approach was to target individuals and their families with false information (such as threatening to tell King’s wife about his infidelity if he didn’t commit suicide) or planting information in the news media. In the case of Jean Seberg—according to memos recovered under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)—the stated goal was her “neutralization,” and to “cause her embarrassment and serve to cheapen her image with the public.” She, along with other Hollywood activists, including Jane Fonda, were also essentially blacklisted from working in the U.S. until the program’s exposure in 1971.

After the death of her child in 1970, Seberg became erratic and paranoid. Her then ex-husband Romain Gary has stated that Seberg attempted suicide on or near every August 25 thereafter—the anniversary of her child’s premature death. In late August 1979, Seberg went missing. Her badly decomposed body was found nine days later in the backseat of her car, not far from her apartment in Paris. She’d overdosed on barbiturates. In a note left to her son she reportedly wrote, “Forgive me. I can no longer live with my nerves.”

Romain Gary publicly blamed the FBI, Newsweek, and the Los Angeles Times for the death of Jean Seberg. Incidentally, a year later, in 1980 Gary also committed suicide. To distance itself from the illegal practices of the Hoover era, the FBI released a statement confirming the vilification and harassment of Seberg and vowed that those tactics were no longer being used. However, the Church Committee (a Senate investigative committee organized to determine the scope of the newly exposed program) found that COINTELPRO was even more deep-seated and broad than previously thought.

Noam Chomsky said in an interview with the BBC in 1996 that:

“COINTELPRO was a program of subversion carried out not by a couple of petty crooks, but by the national political police, the FBI, under four administrations… by the time it got through, I won’t run through the whole story, it was aimed at the entire new left, at the women’s movement, at the whole black movement, it was extremely broad. Its actions went as far as political assassination.”

Virtually every non-white and anti-war organization in the country had a file and had been targeted, and half of Hollywood. By its end, Nixon himself was receiving daily warrantless briefings on Seberg, Fonda, and many others who were deemed subversive or undesirable—a direct violation of the First Amendment rights of scores of Americans. Jean Seberg is one of many hundreds of deaths attributed to the FBI’s counterintelligence program. The list is extensive and runs the gamut of revolutionary leaders to ordinary, non-violent citizens. Seberg and victims like her, however, were integral in exposing the systematic rights violations the FBI had been committing for decades. It’s too bad so many had to die to get to the truth.

In 1975, Joyce Haber was fired from the Los Angeles Times by Jim Bellows. His reasons were that she knowingly and repeatedly ran with stories she knew to be false, and that her information was no longer trustworthy. Bellows, for his role in the death of Jean Seberg and her child, has stated in subsequent interviews that the incident is the worst thing he’s ever been professionally involved in and that it was a mistake to not seek corroboration on the tip he received from the FBI.

No shit.

Originally published by RAZORCAKE.