Film Review: Woman in the Dunes (1964)

I imagine the allegory of Woman in the Dunes shifts both generationally and geographically. It’s meaning, upon its release in 1964, would have differed for American audiences versus Japanese ones due to cultural differences. Within this geographic structure, age and life experience is a major factor as well. Attitudes toward work and duty, coupled with one’s connection to the horrors of Nagasaki and Hiroshima and their aftermath (peripheral or direct) are key to the initial reactions to Hiroshi Teshigahara’s phenomenal film. As generations pass, new meanings form, and new allegories can be explored. Societal perceptions change, and film’s messages change with them. At some point, it’s easy to reason, the meaning of a film could shift a full 180 degrees from the filmmaker’s original intent. This is an amazing byproduct of cinema. It’s the gift that keeps on giving.

Woman in the Dunes is Teshigahara’s question to society (his then, and ours now). But, individual experiences and cultural upbringings will, and should, dictate the answers. As with many experimental, Avant-Garde, or art films, exact meaning is left intentionally vague. It’s so much more fun to let individual viewers filter content through their own experiences, and then decipher it for themselves, adding their own bursts of color and energy to the conversation. To me, Woman in the Dunes might be about how we trick ourselves into enjoying and depending on the societal restraints that are placed on us. We’re taught that work is essential to survive, and in doing so, create excuses for spending most of our lives doing it instead of the things we enjoy. We’re bugs trapped in a jar, but after time, we wouldn’t know what to do without the jar. With the lid lifted, would we jump at the chance at freedom, or would we choose the familiar routine?

Following the film’s plot requires a slight leap in logic, but you’ll hardly notice. Eiji Okada plays an amateur entomologist searching for a rare insect in a remote desert region of Japan. After missing the last bus back to civilization, he’s offered shelter by some locals. They take him to a widow’s house (Kyōko Kishida) which happens to be at the bottom of a large sandpit. It requires a rope ladder to access. The widow hospitably cooks for him and fans him while he eats, all the while making veiled references to how long he’ll be staying. The man repeatedly insists that he’s only staying the night, ignoring every clue to the contrary. Later, he finds the woman shoveling sand into large buckets to which are hoisted up and out of the dune. In the morning, he discovers that the ladder is gone and that he is now a prisoner, expected to help the woman shovel sand.

Thus begins the strange journey and rich allegorical tale of Woman in the Dunes. I say the plot requires a leap in logic because the woman’s explanation of why she must dig doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, but it doesn’t need to. In fact, that it doesn’t quite add up is part of the mythology of it all. “Are you shoveling to survive or surviving to shovel?” is the man’s question to the woman, and possibly the film’s ultimate theme. She offers explanations for why she does it, many of them, and strangely each one makes sense at the moment. Further examination proves that none of it makes sense at all and that she might be suffering from a severe case of Stockholm Syndrome. But if she is, and this is an allegory for life, independence, and individualism, then aren’t we all suffering too? In the end, it doesn’t matter if she shovels because not doing so puts the house next door in danger, or that the village needs the money the sand brings in on the black market, or that her family is buried there. What matters is why you think she does it, and why the man eventually does it too.

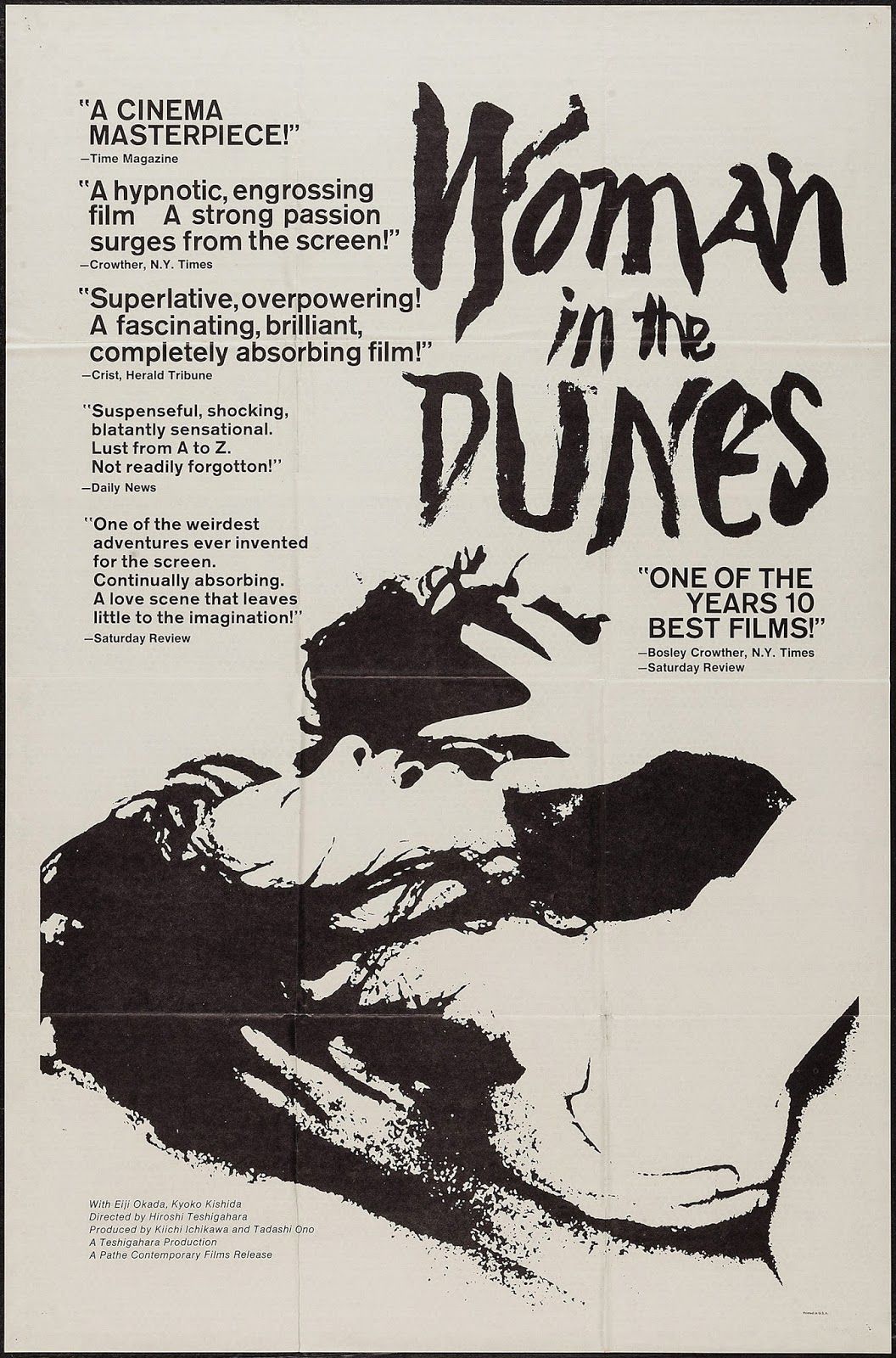

On a visual level, Woman in the Dunes is nearly unmatched. And I don’t say that lightly. The opening shots are of strange alien rock formations – crystalline figures that light glints off in beautiful ways. It is, of course, sand magnified to appear giant. This sand takes on a life of its own throughout the film. It flows like water in a living, vital manner. It is everywhere, and as you watch, you begin to feel it on your own skin and in your hair. The texture it provides is powerful. It’s very easy to imagine what every surface must feel like if you were to run your hands across it. It creates the landscape and destroys it. Visually, it often resembles water, and is described in the same way that a river, rain, or ocean might be. Umbrellas are placed to prevent it from falling on you, dishes are washed with it, and too much of it will swallow you up. It’s a fascinating comparison.

The landscape is harsh, textural, and contradictory, and so is the soundscape. Composer Toru Takemitsu combines and manipulates traditional and non-traditional instrumentation to create a haunting and jarring score. It’s alien, and compliments the flawed logic and animalistic qualities of Teshigahara’s vision perfectly. The purpose of a film score is to accentuate mood and to provide clues. Takemitsu achieves this and much more. From the outset, jagged and ominous strings and winds accompany the man’s journey through the desert. He’s right where he wants to be, but the sound tells us he shouldn’t be there. This is contrasted with long moments of silence, making the eventual blasts even more effective.

This is a total package movie. Beautiful, rich, and layered, while remaining accessible to mainstream audiences. It’s not pretentious or “high concept,” as its concepts are recognizable and relevant to everyone. It’s an art film disguised as a minor horror with a simple, unsettling premise. It begs to be analyzed, but in doing so, forces self-analyzation. I can’t help but wonder how I would have interpreted Woman in the Dunes ten or twenty years ago – or how will I come to see it ten or twenty years from now? Films capable of pulling off this trick are something rare and very special.