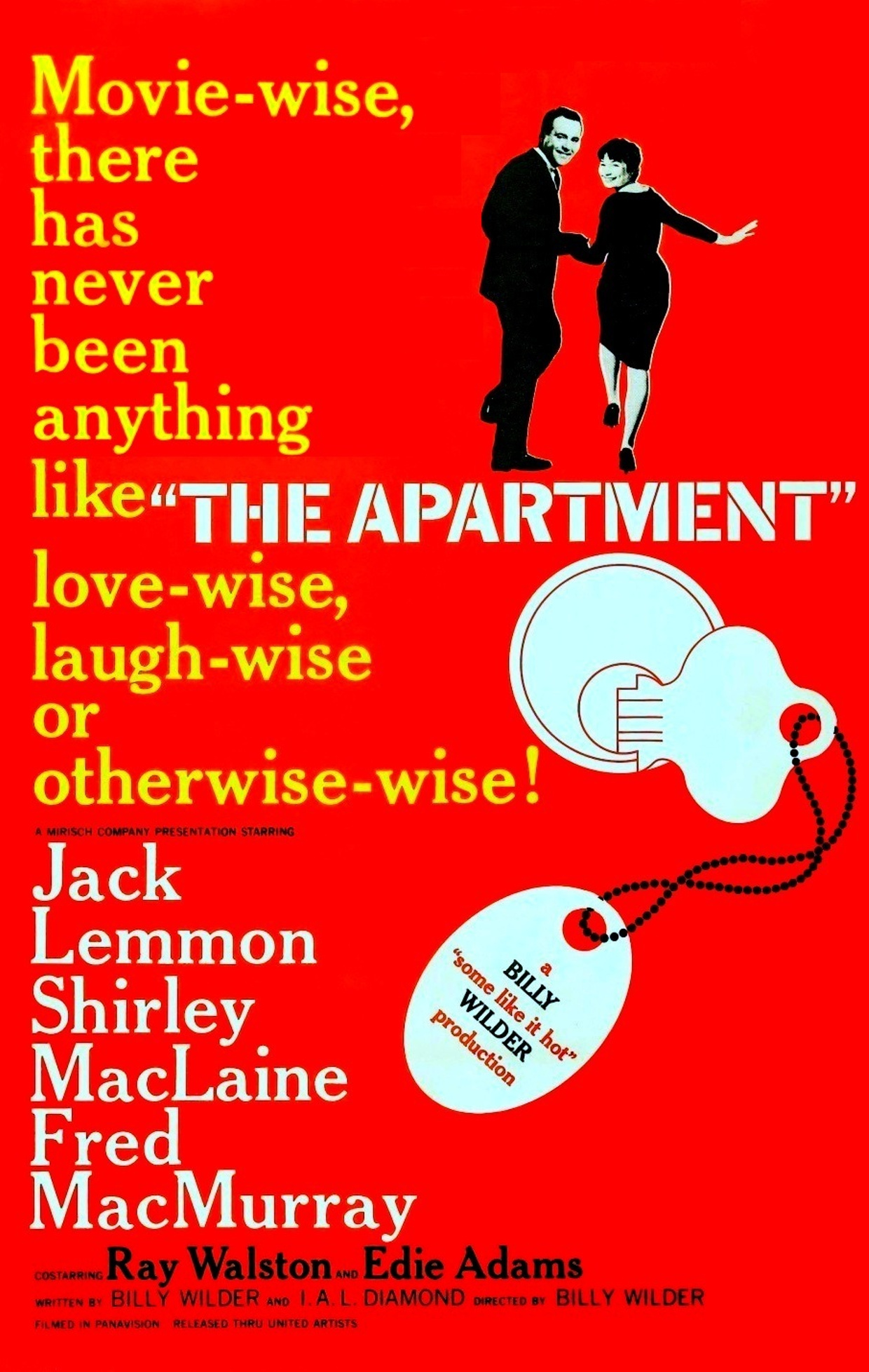

Film Review: The Apartment (1960)

If someone were to tell you how Billy Wilder’s The Apartment begins and ends, there’s a good chance you’d walk away with a skewed idea of what you’re in for. A quick synopsis may include words like “screwball” and “romantic comedy,” and though descriptors like these may be accurate in part, they don’t convey the whole story. While not quite “dark” – Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine’s natural comedic tendencies mixed with Wilder and partner I.A.L. Diamond’s whip-smart writing keep it from getting too bleak – there is a certain grimness that hangs over the events that unfold. That tends to happen when the plot and the bulk of the run-time centers around a suicide attempt.

In brief, The Apartment follows C.C. “Buddy Boy” Baxter (Lemmon), a mid-level cog in an enormous insurance company machine. His main goal, sadly, is to escape the confines inhabited by the faceless masses and achieve middle-management status. To help ingratiate himself to those in a position to help him climb the ladder, he loans out his apartment for the executives to use in their illicit affairs. When the big boss man Mr. Sheldrake (Fred MacMurray) one day wants to use his place for a tryst, Baxter seems to finally be in reach of his goal.

Of course, things are complicated by Baxter’s infatuation with Ms. Fran Kubelik (MacLaine), a quirky, no-nonsense elevator girl who works in the building, who also happens to be the very woman Sheldrake is having an affair with. On Christmas Eve of all nights, things come to a head when Fran attempts suicide in Baxter’s apartment. I’ll let the specifics unfold naturally for you from there, but this nasty turn isn’t the only controversial aspect of the film. It may be hard to imagine now but in 1960 The Apartment‘s frank and open discussion of adultery was atypical for the time. I suspect, however, the depiction of this open secret is accurate. Within the boys’ club, it would have been a common and accepted practice. For the women of the era, shame, rejection, and a reputation were more likely than congratulatory pats on the back. What’s interesting is that nothing explicit is shown or said outright, but it doesn’t have to be. Wilder trusts us to take the hints, just as we trust him to paint us a thorough picture. And we should – The Apartment won Best Picture, Best Director, and Best original screenplay Oscars.

Carrying us through Wilder and Diamond’s meticulous script are three stellar performances. Watch Lemmon as the Christmas party scene unfolds. His interaction with MacLaine goes from jovial to sympathetically depressing in an instant and he takes us right along for the ride. MacLaine is equally sympathetic, but for different reasons. Her mistreatment by the against type MacMurray and her practical, if a bit dramatic, outlook on life and her role in it is refreshing for a film of 1960. She’s no bimbo. She’s a girl caught up in a situation that she clearly recognizes as unhealthy but falls for anyway because MacMurray is such a charmer. And MacMurray – a wholesome family man go-to in anything but a Billy Wilder film – is perfect as the slimy Mr. Sheldrake. Somehow, he’s even sleazier than Walter Neff, which is saying a lot for a character that helped define the moral corruption of the Film Noir genre.

The Apartment has a lot to say and it isn’t afraid to say it. Infidelity, promiscuity, suicide, and even an abortion reference set this multiple Oscar winner apart from anything coming out of mainstream Hollywood at the time. Wilder made a career out of pushing boundaries with the Hays production code and The Apartment further led to its erosion and eventual abandonment. It’s a very funny film, but the dark corners it inhabits set the stage for the groundbreaking and unapologetic cinema that would emerge in the second half of the 1960s.