Film Review: Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach and Western Genre Conventions

The Western film genre has been around almost as long as the moving pictures themselves. Born from the dime novels of the second half of the 19th century, Westerns deal with the notion of America’s expansion towards the Pacific, and the hardships, violence, heroes, and myths that expansion created. The taming of the wilderness through good old fashioned American ingenuity, technology, rugged individualism, and Manifest Destiny are themes that run throughout the genre, managing to capture our imaginations to this day. Often quickly and cheaply made, just as the dime novels that made up much of their early source material, Westerns were mostly second rate matinee fare in the first half of the 20th century. John Ford’s 1939 film, Stagecoach, was instrumental in moving Westerns out of the realm of the “B picture”, and into that of the mainstream, adding credibility and depth to the genre. Even while utilizing many of the established Western genre conventions such as the taming of the West, and the use of beautiful landscapes, Ford brought us a story that surpasses genre while still living wholly within it.

The overlying threat to the protagonists throughout Stagecoach – and a very common convention within the genre – is the impending attack by Geronimo (Chief White Horse) and his wild Apaches. The Native Americans in the film are not treated any differently than usual for a film of this time. They are savages who are standing in the way of plucky American entrepreneurs, frontiersman, and adventurers who are attempting to realize their destiny. The Native Americans represent the unknown, uncivilized, and expansive wilderness, so for the West to be conquered, the Natives, and by extension, the land and country, must be tamed. The passengers on the stagecoach represent this coming civilization. Their safe arrival in Lordsburg, with the help of the Cavalry, means the end of the Native American culture and the completion of Manifest Destiny. This is American mythology at its finest, or worst, depending on how you choose to interpret it.

Interestingly, Westerns have another character type who embodies the same ideals as the Native Americans, the Cowboy. The Cowboy archetype, in this case, The Ringo Kid (John Wayne), is generally a loner who lives a hardworking, yet carefree lifestyle which is firmly rooted in the land. The difference between the Cowboy and the Indian is that the Cowboy is attempting to tame the land just as the coming civilizers are, but at least he has an appreciation for what it is that he’s taming, and he recognizes its power over man. He is ultimately a tragic figure, though, because once the land has been tamed, and therefore changed forever, he can no longer exist in it. His wild and reckless lifestyle must be exchanged for one of civilization. Ringo and Dallas (Claire Trevor) are somewhat unique in Stagecoach, however, as they can avoid these trappings by escaping to Ringo’s ranch in Mexico, or as Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) puts it in the film’s final scene, “Well, they’re saved for the blessings of civilization.”

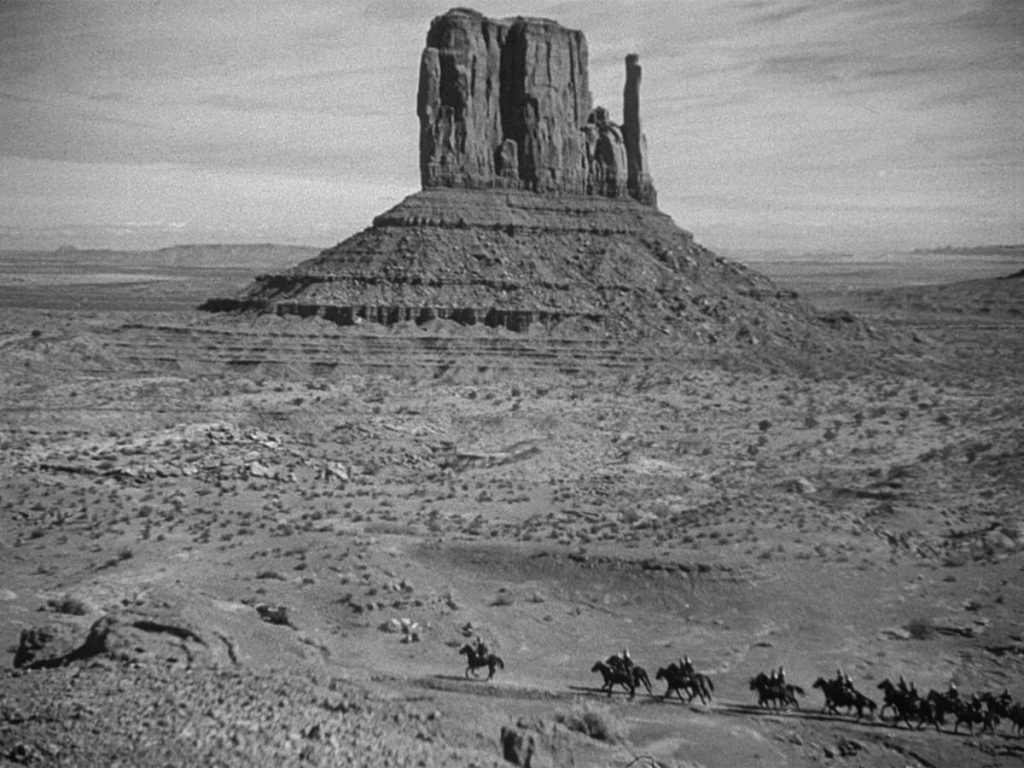

Because Westerns deal with the conquering of the frontier, the frontier itself becomes a genre convention. The wide-open spaces and picturesque scenery is the perfect backdrop to telling these types of stories. Stagecoach was the first of many films that Ford shot at Monument Valley in Utah and Arizona. The monolithic stone structures dwarf the human inhabitants of this scenery, emphasizing their insignificance in this untamed land. These larger than life spaces also represent the wide-open possibilities that await the characters that pass through them. If you can conquer this wild land filled with savage natives and lawlessness, you can conquer anything that may lie ahead. The Western can’t be unlinked from this setting. You could set the film in outer space, or in a warzone, but you’re still dealing with an untamed, expansive, and hostile locale (outer space), or a crazy, chaotic, and unruly one (warzone). The environment needs to be present and visible in the story for it to work. The setting is not only thematic but nearly becomes its own character. Whether this character is a protagonist or an antagonist depends on the story being told, but there’s no denying its importance to the film.

Stagecoach wasn’t the first film to use these, and other, genre conventions, but it perfected them. Ford broke new ground with his little picture, influencing almost every Western that came after it. His use of themes and landscapes may not have been a new concept, but the way he placed his well-rounded characters in them changed the way producers and audiences looked at the genre. The Western was transformed into a viable, and respected way to tell stories.

United States • 1939 • 96 minutes • Black & White • 1.37:1 • English • Spine #516

Criterion Special Features Include

- New, restored high-definition digital transfer, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray edition

- Audio commentary by western authority Jim Kitses (Horizons West)

- Bucking Broadway, a 1917 silent feature by John Ford, with new music composed and performed by Donald Sosin

- Journalist and television presenter Philip Jenkinson’s extensive 1968 video interview with Ford

- New video appreciation of Stagecoach, with director and Ford biographer Peter Bogdanovich

- New video interview with Ford’s grandson, Dan Ford about the director and his home movies

- New video piece, featuring journalist Buzz Bissinger, about trader Harry Goulding’s key role in bringing Monument Valley to Hollywood

- New video homage to legendary stuntman Yakima Canutt, with celebrated stunt coordinator Vic Armstrong

- Video essay by writer Tag Gallagher analyzing Ford’s visual style in Stagecoach

- Screen Director’s Playhouse 1949 radio dramatization of Stagecoach, with John Wayne, Claire Trevor, and Ford, downloadable as an MP3 file

- Theatrical trailer

- English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

- PLUS: An essay by David Cairns and, for the Blu-ray edition, Ernest Haycox’s “Stage to Lordsburg,” the short story that inspired the film