Film Review: Roma (2018)

Alfonso Cuarón’s new film is almost too beautiful for words. Its beauty doesn’t only lie in what we see, but in what we hear, and what we can nearly taste, smell, and touch. It covers all five senses better than any film this year – maybe even this century. And of course, we can feel the film too. It’s easy to do this considering the care and compassion its characters and their lives are given. Even me, a kid from the upper-Midwest, can tell that Cuarón’s vision of 1970 Mexico City and its people isn’t romanticized nostalgia, but honest, tangible memory of a time and place that’s often overlooked. Rarely are recollections translated so vividly and convincingly as in Roma. This is Cuarón’s story, but it’s not about him. It’s about the women who helped shape him. Roma is a deep, rich, wonderful film that should not be ignored.

Men leave, while women band together and survive. If I had to break down what Roma is about into its simplest components, that’s at least a good place to start. This cycle isn’t new, and it certainly isn’t specific to Mexican culture, but it takes its toll. The men of Roma have a choice and choose selfishly. The women are offered no such choice but are much stronger and more honorable for it. Physical strength, money, power, or any other outward visage of masculinity falls flat on its face when analyzed through this lens. Roma isn’t an “anti-men” film, nor is it blatantly feminist, but it is damned honest. It shows cowardice masked as virility and machismo and does so without posturing or sloganeering. Its simple humanity is more than enough.

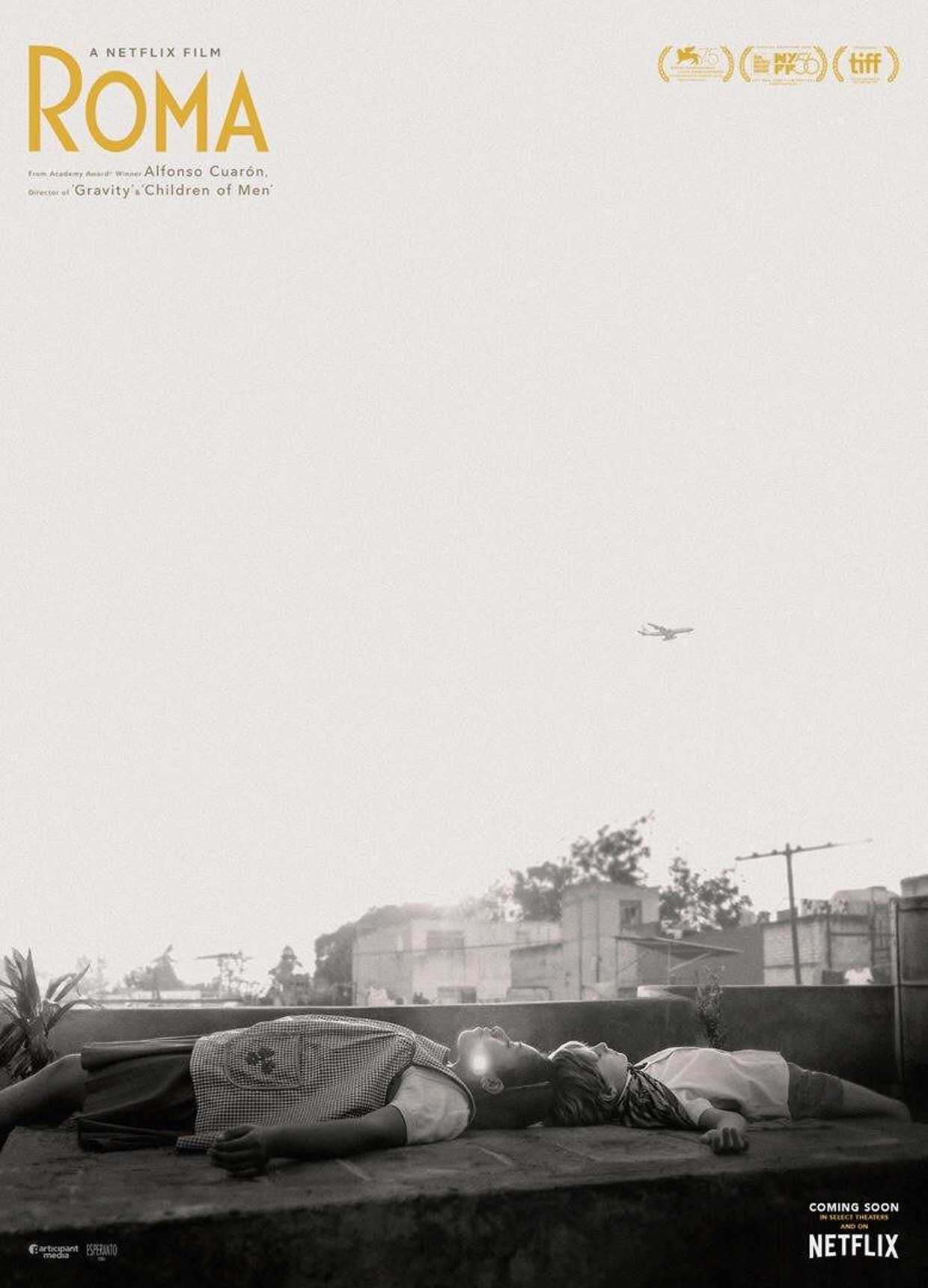

And it’s this humanity that drives the entire film. Shot in widescreen black and white (cinematography by Cuarón himself), we first meet Cleo (newcomer Yalitza Aparicio) as she cleans the floor of her employer’s carport (where the family dog does his business). In the opening shot, we see a tiled floor accompanied by the sounds of scrubbing. Soon, water is thrown into our field of vision (the camera remains stationary, poised on a singular spot), and in its reflection, we can see the sky through a window. An airplane passes by while Cleo continues her duties. This opening sequence is long and would be mundane if it weren’t so beautiful. But it’s the mundanity and the beauty that Cuarón wants us to see – that both can exist simultaneously.

The lives of Cleo and her employers are minimal compared to the large, sweeping nature of the world they inhabit. The grandness of Mexico City dwarfs their home, but it’s through this home that the city comes alive. The cars, the posters on the cracked walls, the dogs, the airplanes flying overhead – all this and more paints a picture so complete and immersive it’s very easy to become lost in it. Through this small slice of life, we’re exposed to a cinematic epic panorama full of heartbreak and violence, but also triumph and love. Cuarón’s vision is projected outward from Cleo’s limited world and doesn’t stop until it reaches the sea and the skies.

Like Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (1982), say, Roma takes its time in revealing its secrets. This slow unfolding allows us to fully understand the characters, and by the time we’re hit, we’ve been welcomed into the family. It has a natural quality similar to Ozu, but a style unto itself. It’s a transportive film that moves at the pace of the world it inhabits and forces engagement from its audience with its pure compassion and consideration. It’s a powerhouse of world cinema with a universal understanding of life.