Film Review: Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979)

It’s difficult to discuss Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) and not make comparisons to F.W. Murnau’s masterpiece, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horrors (1922). It’s difficult because Herzog openly invites us to make comparisons. I am very reluctant to call the film a remake. In fact, I won’t call it that, and neither should you. Reimagining is a term that gets thrown around a lot these days when studios decide that they need to restart some long-dead or unsuccessful franchise, but it’s not that either. What we have here is an honest to God tribute film. And a very good one at that. Herzog borrows shots from the original freely and without shame, and they are beautiful. Why shouldn’t he? Count Orlock (Max Schreck) standing on the deck of the ship is one of the most iconic and utterly terrifying images in cinema history. How could one resist recreating it? What fun!

What Herzog, born in Munich Germany 20 years after the release of Nosferatu, is doing here is attempting to bridge a generational gap. He has often said that his was a fatherless generation. World War II took its toll on the German population, and many youngsters were raised without their fathers. Herzog was one of these youngsters, and I believe that making this film was a way to explore the cinema of not just his birth nation, but that of the generations that came before him. He was connecting with the great films of the lost fathers and grandfathers of Germany.

The story is largely unchanged from Murnau’s film—based on the Bram Stoker novel, of course—so I’ll spare you the details as I’m sure you are at least partially familiar with the basic plot. If not, go watch the Murnau film to familiarize yourself with it, and get a hearty dose of good old fashioned German Expressionism while you’re at it. You should have seen Murnau’s film by now anyway. It’s required viewing.

I love how Herzog approaches filmmaking. To keep his films on budget—which are always comparatively small—he is required to move quickly. Get in, get the shot, and get out. Often the camera is handheld to save time, and Herzog is the one doing the holding. His films are not always slick productions, but they are often more thought-provoking than anything mainstream Hollywood is churning out. Imagine the sense of adventure working on a Herzog set. He is famous for never using storyboards, saying that they are for cowards and they restrict imagination. He prefers that a sense of urgency and dedication are what should keep everything moving, and the creativity flowing. Nosferatu is no different.

The film opens with footage of naturally preserved mummies that Herzog found in Mexico, the results of a Cholera outbreak in 1833. He shot the footage himself, and even though the mummies do not appear elsewhere in the film, they set an eerie tone quite nicely. Popol Vuh—the German synth-rock band that Herzog uses in a handful of films—once again helps out with keeping things nice and creepy. Their electronic harmonies echo the oddities we are seeing.

The opening sequences of the film all deal with getting Johnathan Harker (Bruno Ganz) from Wismar, Germany to Transylvania in order for us to meet the titular character. Along the way, we are treated to some spectacular scenery and colorful characters. Renfield (brilliantly and devilishly played by Roland Topor), seems to be the only person in Harker’s life that wants him to travel the great distance to Transylvania (for reasons that are his own). Lucy (Isabelle Adjani), his wife, begs him to stay in Wismar to no avail. When he encounters a small village near the Count’s castle, the locals—in a great scene—beg him to go no further, even denying him transportation which forces him to proceed on foot.

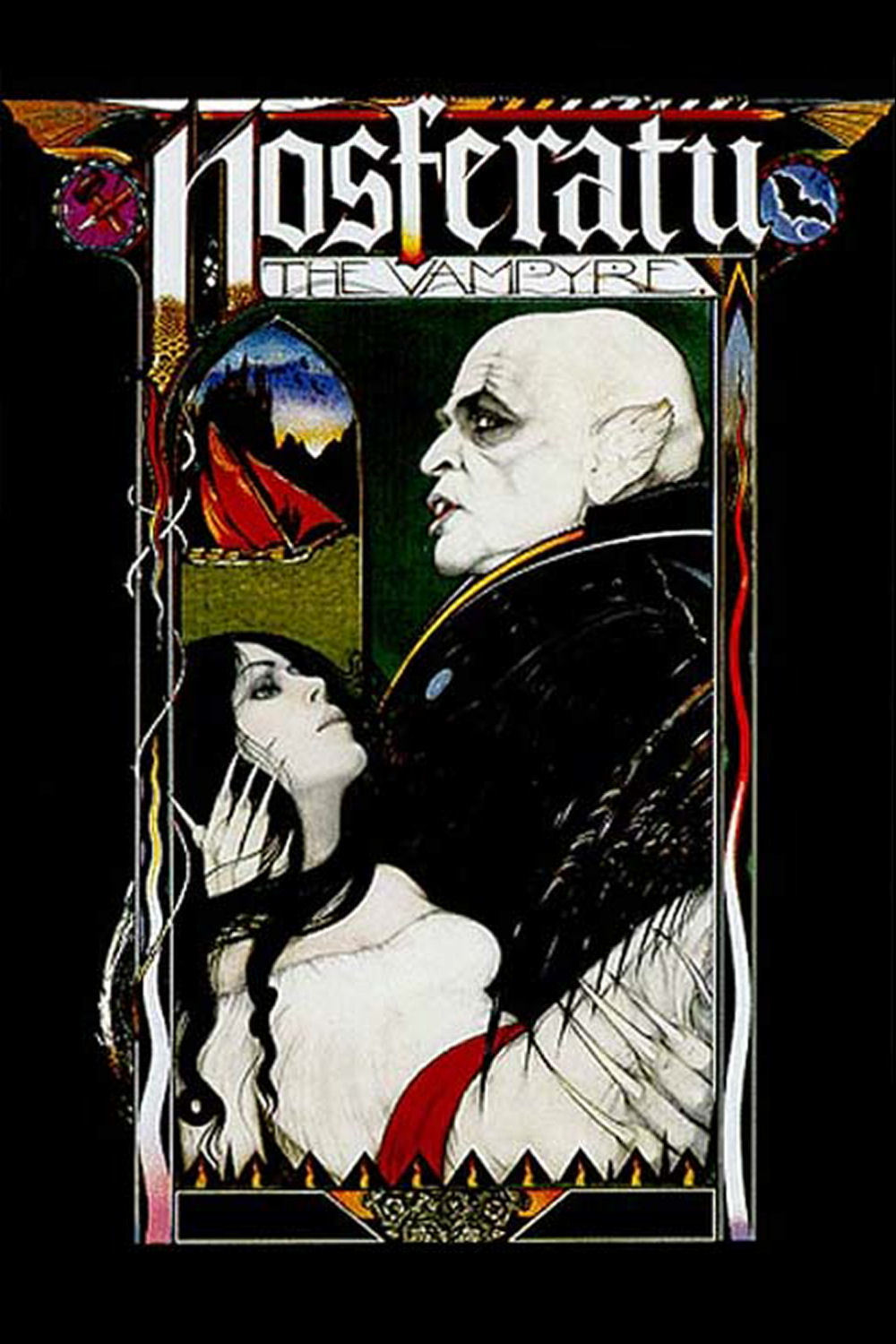

When Harker finally arrives at the castle, he is greeted by the one and only Count Dracula (and the one and only Klaus Kinski). Now, for the record, I have never been much of a fan of the dapper Dracula that most people think of when they envision the Count. The smooth talker and the fancy dresser never really did it for me. Bela Lugosi and Christopher Lee were exceptions, but I feel nearly every other portrayal has been an attempt to ape these two greats’ performances, therefore, they come off as unoriginal. The Max Schreck version, on the other hand, was both the first, and the best, and Kinski’s take on it is nothing short of brilliant.

The makeup and wardrobe are faithful to the original film, but with the addition of color photography, Kinski and Herzog manage to bring a completely new level of horror and sympathy to the fiend. The stark white face and black robes set against vividly colored backgrounds is a reminder of both Dracula’s humanity, and his “otherness”. He does not belong in this world, yet, there he is. Kinski plays the character with such sympathy and sorrow that he nearly becomes a tragic figure rather than a murderous villain. The revulsion one feels toward this blood-sucking bringer of death and disease is nearly forgotten, and in turn, replaced with feelings of sympathy towards his sad fate of loneliness and isolation. Well, almost anyway. He does still kill a lot of people. That’s kind of his thing.

The rest of the cast is excellent as well. Bruno Ganz’s slowly deteriorating Harker is a pleasure to watch, and I already mentioned Roland Topor’s Renfield. But, it’s Isabelle Adjani’s Lucy who is the real standout among the rest of the cast, and the real hero of the story. Lucy, surrounded by death, overcomes terror and seeming madness to dispatch the creature on her own. Adjani mixes both “scream queen” schlocky goodness, with downright righteous feminist power creating the best-played foil to Dracula the screen has ever seen. No joke.

The more I analyze this film, the more I love it. The pace, the performances, the color, everything about it is simply wonderful. The plague subtext, the rats, and the dreamlike, surreal nature of it all (something common in Herzog’s narratives) all lend to a truly beautiful film. In one particularly stunning sequence, Lucy finds herself wandering through the town square where an insane celebration is going on (in a nod to Bergman’s 1957 classic The Seventh Seal, another film that deals with the plague). The revelers are infected, and will surely die. Are they celebrating life or welcoming death? Plague-infested rats are everywhere, but suddenly, the people are all gone and only the rats are left, scouring what’s been left behind. It’s a dreamlike scene whose meaning we can only guess at. Which is just the way Herzog likes it.