Film Review: Ikiru (1952)

“You’ve never had a day off, have you?”

“No.”

“Why? Are you indispensable?”

“No. I don’t want them to find out they can do without me.

— Toyo’s joke

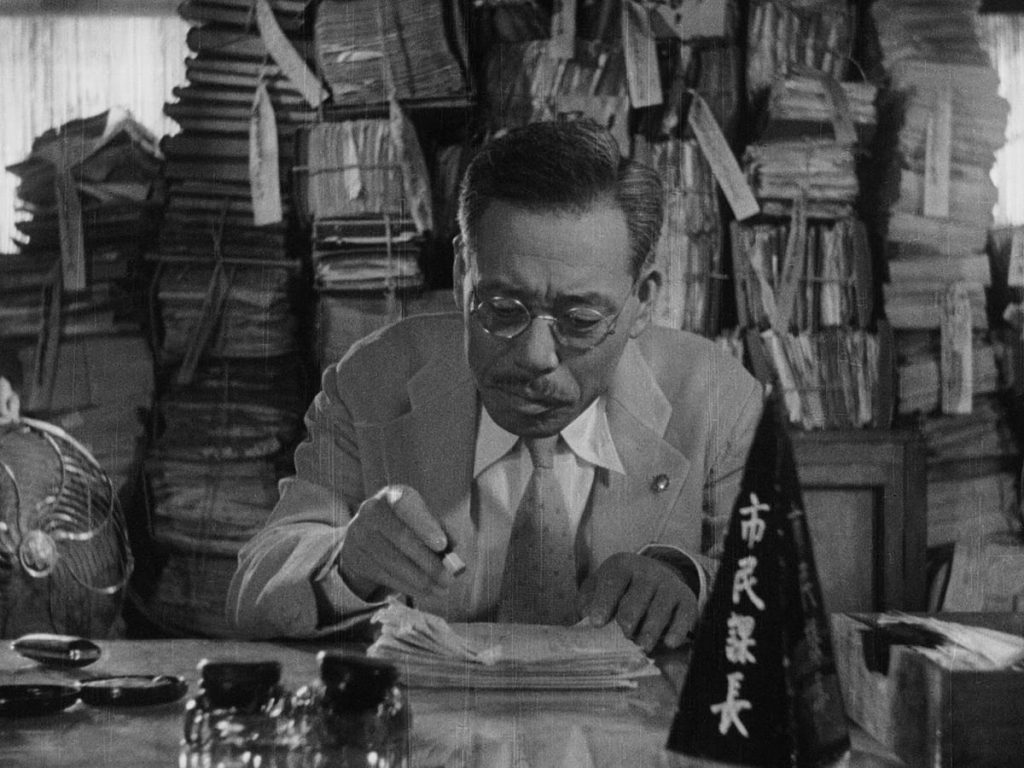

In Ikiru (which means “to live”), Takashi Shimura plays Kanji Watanabe, a middle-aged Japanese bureaucrat who never lived a day in his life. Director Akira Kurosawa tells the story of Watanabe with sympathy and reverence but is careful not to gloss over his shortcomings. Watanabe’s life has been one of compliance—from his nearly pointless civil service, to the never-ending paperwork his job creates, and to his obedient adherence to protocol—he never questions the reason for it all, and never once accomplishes anything of worth in a career that spans decades. That is, until the day he finds out he’s going to die.

Watanabe is a sad man and remains so for most of the film. Upon hearing the bad news, he attempts to tell his son and daughter-in-law (Nobuo Kaneko and Kyoko Seki) but doesn’t get the chance as they’re much more concerned with making plans for his retirement money. Heartbreaking flashbacks are shown, making the subdued state he mopes around in very easy to understand. It’s clear to see that he’s lived a life of disappointment. Finding pity for him is not difficult.

Watanabe decides to finally live his life and find some purpose. First, he takes up with a philosophical novelist he meets in a bar (Yūnosuke Itō) and together they hit the town. The drinking and carousing last for only one night, however, ending in Watanabe singing an old, sad song about missed opportunities and squandered youth (“Life is brief, fall in love maidens…”). Next, he scandalously cavorts around Tokyo with Toyo (Miki Odagiri), a young girl who worked in his office. He feels uplifted by her youth and exuberance, and the pair spend a few days together. Watanabe buys her nice things and takes her out to dinner (much to the embarrassment of Watanabe’s family, who is also concerned because he’s stopped going to work), but this doesn’t last either. Toyo quickly grows weary of Watanabe’s attention, preferring to spend time with those her own age. She tells him he needs to find purpose—that he needs to do something significant. Heeding her advice, he decides to do exactly that.

The rest of the film is a testament to the spirit of Watanabe, and the task he chooses to undertake. In the first half of the film, Kurosawa paints an elaborate and depressing picture of Japanese bureaucracy and those that toil in it. It’s a cyclical machine that accomplishes very little, yet demands immense amounts of time from those trapped in its hold. In the beginning, Kurosawa gives us an example: A group of mothers is asking that a cesspool be cleaned up and a park be built in its place. The uninterested and lazy employees of the city shuffle them from one department to the next—over and over—until finally they are told to come back with a written proposal. Tedium for the sake of tedium.

When Watanabe finally goes back to work and takes on the project, he isn’t seen as a go-getter trying to do the right thing. He’s seen as crazy. What he does simply isn’t done—and in doing so, he nearly breaks the system. His actions are inappropriate on a cultural level and set a very bad example for the ineffectual functionaries who are terrified of making waves. But he sticks with it, and eventually, his project makes it to the Deputy Mayor (Nobuo Nakamura)—who represents how many levels of inefficiency and officialdom there are.

I won’t tell you any more about the plot, but I will tell you this: Watanabe’s story is one of courage and beauty. Shimura’s performance manages both sorrow and exceptional accomplishment, all without a change in voice, mannerism, or attitude. The metamorphosis Watanabe experiences is total but deceptive. He’s the only person who knows he’s gone through it, and he uses that to his advantage. His co-workers eventually become inspired by what he’s managed, but ultimately can’t, or won’t live up to his example. It’s at this moment that I find the film at its most human. Watanabe has reason to be fearless. These men lack this motivation, and so are doomed to wither in their routine—day in, day out. In the face of death, only Watanabe lives and thrives.

Japan • 1952 • 143 minutes • Black & White • 1.37:1 • Japanese • Spine #221

Criterion Special Features Include

- New, restored 4K digital transfer, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray

- Audio commentary from 2003 by Stephen Prince, author of The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa

- A Message from Akira Kurosawa: For Beautiful Movies (2000), a ninety-minute documentary produced by Kurosawa Productions and featuring interviews with the director

- Documentary on Ikiru from 2003, created as part of the Toho Masterworks series Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create, and featuring interviews with Kurosawa, script supervisor Teruyo Nogami, writer Hideo Oguni, actor Takashi Shimura, and others

- Trailer

- New English subtitle translation

- PLUS: An essay by critic and travel writer Pico Iyer and a reprint from critic Donald Richie’s 1965 book The Films of Akira Kurosawa