Film Review: First Cow (2020)

It is my opinion that no film genre tackles the uncomfortable relationship between American individualism and the hardships of capitalism quite like the western. Often in these films, as manifest destiny collides with entrepreneurship and greed, those lacking in gumption or the necessary fortitude to thrive in harsh new territories are left behind or exploited by those who do. In a world in which survival is predicated upon either direct contact with the land, or payment (nefarious or otherwise) from those who know how to manipulate it, the ever-encroaching “civilized” world is either a death knell or an opportunity, depending on which side of capital you stand on. These economic discrepancies undoubtedly create desperation, and this desperation always leads to violence in some form or other. Thus is the western.

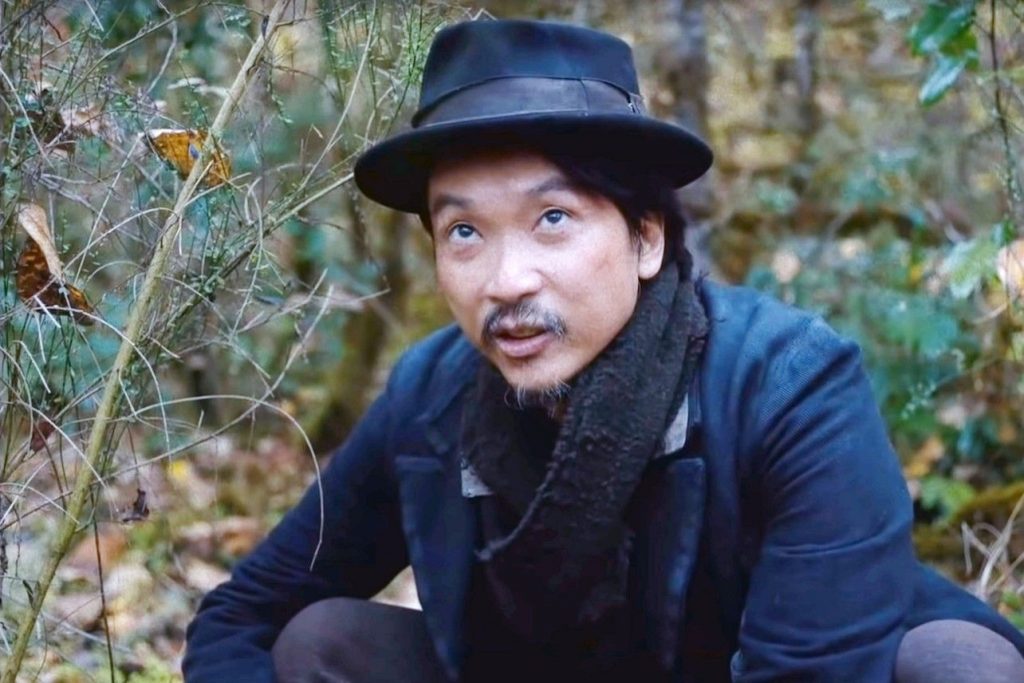

In First Cow, two unlikely companions in 1820s Oregon find themselves at a crossroads. In one direction lies a meager existence of poverty and half-starvation, and in the other a prosperous life of commerce and even possible notoriety. These men – King-Lu (Orion Lee), a Chinese immigrant, and “Cookie” (John Magaro), a baker from Maryland – are not bank robbers or unscrupulous cattle barons, or even exceptional opportunists for that matter. They are simply two men fed up with the hard-scrabble life they’ve been dealt, a realization that causes King-Lu to lament, “It’s the getting started that’s the puzzle. No way for a poor man to start. You need capital. Or you need some kind of miracle…. Or a crime.”

Short on both capital and miracles, they are left with only one option: to become criminals. And the desperate crime they resolve to commit, and the outrageous acts they employ to pull themselves out of destitution? Stealing milk and making biscuits.

These desperate men may not possess the machismo or steely gazes of their famous western predecessors, but – and I do not say this lightly – somehow director Kelly Reichardt makes clandestine cow-milking as tense and exciting as a Leone graveyard shootout. This is due in part to the meticulously detailed world Reichardt and co-writer Johnathan Raymond (who wrote the novel the film is based on) have crafted for Lu and Cookie – a dismal, squalid place in which the only thing hard work gets you is harder work, and more of it – but there’s more to it than that.

The film opens with the discovery of a pair of skeletons along a riverbank by a young woman (Alia Shawkat) and her dog. This set-up – which takes place in the present day – casts a large looming shadow over the entirety of the story, as the fates of our yet-to-be-introduced protagonists appear to be sealed. While it could be argued that this predictive fatalism spoils the ending, I would argue that it actually enhances it. We may be certain who the bones belong to, but we’re in the dark about when the circumstances leading to their placement will occur. This knowledge (or lack thereof) keeps us gleefully tense. Reichardt and Raymond create a wonderful “need to know” aura that may have otherwise been absent, and it’s through this foreshadowed tension that the simple act of milking a cow becomes a harrowing activity.

What’s more, the relationship between Lu and Cookie is so thoroughly heartwarming that it is impossible not to root for them. On the surface, their friendship is not unlike that found in other genre films, and neither is their pursuit of a humble yet comfortable life, but the heart that lies at the center of their endeavor is pure and nearly untouched by the cruelty of their surroundings. In a lesser film, they might turn to savagery to match their environment, but they never do. Instead, through their camaraderie shines a kindness that keeps them grounded in human spirit rather than devolving them into resigned products of their environment.

That these two men from opposite ends of the world find each other and strike up a kinship based on each other’s simple company is both remarkable and tragic, but it’s the often silent performances of the film’s leads that anchors them in both sympathy and gloom. Lee and Magaro’s deliveries are small-scale compared to the big personalities of genre forebearers, but free of expected macho conventions, they are given room to mold their characters into the nonconformists they are meant to be. Like the settlers in Reichardt’s 2010 underrated gem Meek’s Cutoff, Lu and Cookie are outsiders in a wild country, and the antithesis of the rugged heroes we’re used to seeing in these kinds of films. But, unlike many classic genre heroes, their individualism is earned through believable, palpable struggle rather than resting on a predictable archetypes.