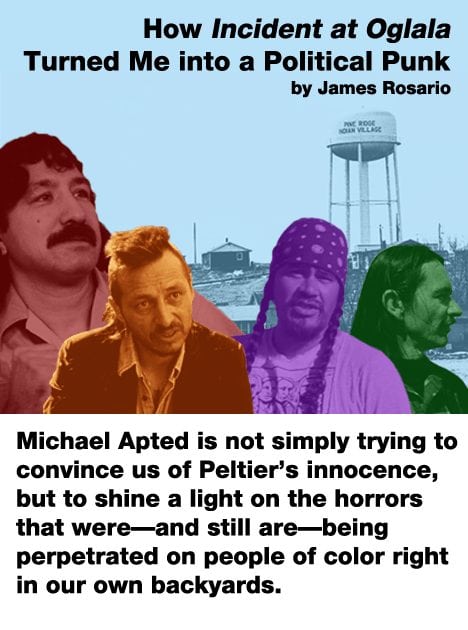

One Punk Goes to the Movies: How Incident at Oglala Turned Me into a Political Punk

“In the early ‘70s, residents of the Pine Ridge Reservation lived in poverty and fear of FBI-backed goon squads. More than two hundred people had been beaten or murdered. Most were supporters of the American Indian Movement. On June 26, 1975, two unmarked cars drove onto Jumping Bull property. A firefight began.” —from the music video “Freedom” by Rage Against The Machine

In the early 1990s, I was struggling to discover as much punk music as I could. Back then, it wasn’t always an easy thing to track down. Record stores (or, more accurately, CD and cassette stores) that carried punk were few and far between where I came from so, naturally, sometimes settling for music that wasn’t necessarily considered “punk” was the next best thing. Rage Against The Machine was one of those bands. I had seen them live at Lollapalooza in the summer of 1993, and then again that fall at First Avenue in Minneapolis, and found myself quite impressed. I had always appreciated the politically motivated songs of Metallica and Megadeth, but this was different somehow. It seemed more honest and urgent.

Later that winter (on December 19, 1993, to be exact), Rage Against The Machine’s first MTV video premiered on 120 Minutes. The video was for the song “Freedom,” and acted as a primer on the events leading up to the arrest and conviction of Leonard Peltier—a Lakota Sioux and member of the American Indian Movement (AIM). After that, a lot of things happened quickly for me (as quickly as it could in 1993). The realization that a movement like this had been taking place in my backyard without my knowledge was enlightening. I needed to know more. I researched AIM, which led me to the Black Panther Party, Students for a Democratic Society, the Weather Underground, Abbie Hoffman—the list goes on and on—but it all started with Leonard Peltier and his story. In addition, I soon learned that a good chunk of the music video that got this ball rolling in the first place was made up of clips from a 1992 documentary film called Incident at Oglala. I quickly tracked a copy down and watched it in my parents’ living room when they weren’t home. The screening left me stunned, and just like that, I was a political punk.

The specifics of Leonard Peltier’s case are best left to the film or to your own research, but here’s the quick synopsis. Leading up to the firefight on June 26, 1975, the people of the Pine Ridge Reservation, along with many other Natives in North and South Dakota, had been living in fear. On top of the extreme poverty they endured, a corrupt tribal council was waging a campaign of terror against anyone who opposed them. Beatings and drive-by shootings—led by the council and backed by government and FBI money and guns—were commonplace. To combat this brutality, the American Indian Movement stepped in. On the day in question, two FBI agents raced onto the property of Calvin Jumping Bull (later stating they were chasing a teenager who had stolen a pair of boots). For years, the men, women, and children housed on the land had been living in fear of the council’s paid GOON Squads (GOON being a literal acronym for Guardians of the Oglala Nation), and since the property was AIM headquarters, it was reasonable for them to assume these unknown and unannounced vehicles were there to do harm. They chose to defend themselves, and by the time the shooting had stopped, two FBI agents and one AIM member were dead.

For the purposes of this column, I gave the film another look. It had been at least ten years since I’d seen it, and I was pleasantly surprised to find that, not only had it held up, but was better than I’d remembered. I’m somewhat embarrassed to say, but there was a lot of exposition that had been lost on my teenage self. For example, I clearly recall that, as a teenager, the most important aspects of the film to me were the descriptions of the gun battle, the subsequent manhunt, the trial, and the conspiracies.

This time around, and with the benefit of a fully developed brain and around twenty-five extra years of life experience and observation under my belt, I found the lead-up to the gunfight—the “why”— to be much more intriguing. As white folks like me grow more and more aware of our privilege, the terrorism the people of Pine Ridge faced daily is necessary for understanding how and why the shootout happened in the first place. In 1993, when I first saw the film as a fresh-faced young punk rocker, I had never heard the term “white privilege” before. I was keen on the investigative and conspiratorial aspects of the film, but the setup to the incident was lost on me, simply because I had nothing to relate it to.

I understood racism and its evils but failed to grasp its institutional and systematic nature. We know so much more now, and thanks to cell phone cameras, we see injustices daily (if we choose to look, that is). It’s clear to see that director Michael Apted is not simply trying to convince us of Peltier’s innocence, but to shine a light on the horrors that were—and still are—being perpetrated on people of color right in our own backyards. He’s pleading with us to open our damned eyes and take a good long look.

Leonard Peltier was tried in my hometown of Fargo, N.D., and sentenced to life in prison just a few months before I was born. This shit was literally in my backyard, and I had no idea until a band from Los Angeles made a music video about it. That doesn’t sit well with me. To the predominantly white residents of my hometown, it might as well have never happened at all.

Politics wasn’t the only thing Incident at Oglala turned me on to. It also introduced me to the power of documentary filmmaking. This art form is an interesting animal. Often, documentaries exist to serve one of two purposes: to inform viewers of a subject they may have been previously unaware of or had little knowledge of, or to reinforce an idea or belief the audience already holds. Sometimes, as my experience with Incident at Oglala proves, a combination of both can occur. I was searching for a historical context to my then-underdeveloped notions of anti-racism, anti-colonialism, and police brutality (a reinforcement), and in doing so was turned on to a specific movement that embodied these very ideas that I had not known of before (informed of the unknown). At any rate, Incident at Oglala was my first real experience with a documentary film whose purpose is to motivate change—to fire its audience up. It wouldn’t be the last either. Not by a mile.

To better understand the motivations behind director Michael Apted’s film, it may help to discuss another documentary that was released just four years prior. Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line, released in 1988, is a brilliantly put-together documentary consisting of complex reenactments and witness statements. It tells the story of Randall Adams and the crime he was accused of—the 1976 shooting of a Dallas police officer. Adams, despite flimsy evidence and police misconduct, was convicted of the crime and sentenced to death in 1977. He spent over a decade in prison, maintaining his innocence throughout his stay. In 1988, when Morris’s film was released, enough doubt had been cast on the case to overturn the conviction. Randal Adams was released from prison in 1989.

The Thin Blue Line, a film, was directly responsible for freeing an innocent man from prison. Leonard Peltier’s case held a lot of similarities to the one featured in Morris’s film (flimsy evidence, misconduct, conflicting witness testimony). It had worked once before, why couldn’t it again?

Unfortunately, this time it didn’t pay off. Leonard Peltier, now seventy-three, still sits in Coleman Penitentiary in Florida. His next parole hearing is in 2024.

Incident at Oglala is a complicated film. It has a lot of ins and outs, weird conspiracies, flat-out lies, and claims of witness tampering. It has heroes and villains, justice and injustice. A host of dedicated activists and those who participated in the battle paint a wonderful picture of not just what happened on that day in 1975, but how tensions got to be so high in the first place. Activist and early AIM member John Trudell offers some of the film’s most compelling insights, as does radical lawyer William Kunstler. Robert Robideau and Darrell “Dino” Butler, the other two men charged with the deaths of the agents (both were acquitted), provide persuasive and credible testimony to what happened that day as well. All told, it’s a ride—a captivating example of what cinema can, and should strive to accomplish.

It’s likely I would’ve discovered the radical movements of yesteryear without Incident at Oglala, but I’m glad it was this film that got the ball rolling for me. Even though its full meaning didn’t reveal itself until years later, it’s still an excellent jumping-off point for young activists and punk rockers with a political bent. I can only hope that today’s young punks will grab hold of all themes present, and in doing so, recognize that not much has changed since the shootout in 1975. It’s important to recognize that, as white people, even though we may not be directly in the line of fire, we still have an obligation to act—to use our privilege as best we can.

Originally published by RAZORCAKE.